Gyermekkorom óta érdekelt a politika és történelem. Valószínű ennek köszönhetem, hogy felfigyeltem olyan eseményekre, amelyek mások figyelmét elkerülték. Például: 1956 nyarán lebontották a jugoszláv-magyar határon a műszaki határzárat. Mikor azzal kész lettek, hozzáfogtak az osztrák-magyar határzár lebontásához, melyet szeptember 19-én fejeztek be. 1956 nyarán az utca embere arról beszélt, hogy Magyarország és Ausztria között nyugati mintájú határátkelést vezetnek be. Arról is beszéltek az emberek, hogy a szovjet csapatok Magyarosságról is kivonulnak. Csupa jó hír! Nos, e jó irányba haladó folyamatot a mi forradalmunk törte meg. Kinek az érdeke lehetett? / Azt csak évtizedekkel később tudtam meg, hogy 1956 nyarán tárgyalások folytak a Német Demokratikus Köztársaság és a Nyugat-Német Szövetségi Köztársaság között Németország egyesítéséről. Valakinek ez se tetszett.

The Hungarian revolution and fight for freedom was one of the most significant events in 20th century European history. To have a better understanding of these events, it is necessary to recap some of the political, social and economic conditions that preceded it. It's also instructive to examine the political power struggle, known as the "cold war," which paved the way for the decades-long tension of East-West relations.

When World War II was finally over in 1945, a sigh of relief flooded over victors and vanquished alike. Even in countries falling under Soviet occupation, the reconstruction started out with great vigor and enthusiasm. It didn’t take long, however, for everyone to realize that heady expectations for a better life lived in freedom would not yet be realized. In Hungary, for example, with the help of massive voter fraud and outright cheating, the communists stole the 1947 election. Using a blue ballot with which they could easily cast their vote as many times and in as many places as they wanted because no identification was required, the communists traveled by buses and trucks from town to town casting their cobalt ballots over and over. Following their victory and with the help of the Soviet occupation forces, the communists went about setting up their government. The regime led by Mátyás Rákosi became the most ruthless to be found in any Soviet satellite country. Their opening shot was to outlaw all other political parties and organizations having anything to do with formulating or raising a national consciousness. Next, they liquidated people by the hundreds, perhaps by the thousands, whom they considered enemies of the “people” – meaning the communists, of course. They then began filling the jails and concentration camps by the thousands. Within a couple of years, those workers (and even peasants with a few acres of their own) who bristled and refused to join the collectives gradually became enemies of the state. In schools across the land, the greatness of communism and the worship of the Soviet Union were taught. The communists uprooted Hungarian society across all classes and walks of life – and anyone who dared raise his or her voice was mercilessly punished or disappeared forever without a trace.

By 1952, real hard times fell upon the Hungarians, especially the farmers. Ever greater quotas were set for production – far higher than was within the collective’s capacity to do so. Even so, the communists took everything from them – their livestock, their grain to feed their family, and even the seed needed to sow the following year’s crop. The living standard became horrendous, falling below the level of 1938. As the farmers ran out of everything, they naturally began to revolt; they were put down mercilessly. Many hanged themselves; the less fortunate found themselves in one of the country’s many communist concentration camps. These camps were run by the Hungarian secret police or ÁVH (Államvédelmi Hatóság). This group evolved from the ÁVO (Államvédelmi Osztály) in 1947. They were the guardians – or more to the point – the masters of life and death. Only the most sadistic and brutal individuals lacking any morals were chosen and willing to serve in these organizations. There were very few exceptions to this rule.

Chosen by the ruling communists, people of certain occupations from the old regime, like the csendőr (special police); portions of the regular police; and military judges were singled out for their “cruelty.” While it’s true they were harshly treated, the fact is that there were only nine (9) executions in Hungary – all common criminals, with not a single political execution among them between 1920 and 1945. After this era, however, those released from Soviet POW camps were transferred to the most notorious camps operated by the ÁVH. Ödön Herendi was one of them. He wrote in one of his letters to an author collecting information for his book on the camp of Kazincbarcika:

“I would say without any doubt if one would compare life in an ÁVH-run or Soviet-run prison, the scale would tilt in favor toward the Soviet prison; true, it was a meager existence, however they

didn’t humiliate us. In the ÁVH-run system, however, this was the most important facet. In the Soviet POW camps we could write letters and receive Hungarian and Russian newspapers, while in the ÁVH-run camps or prisons it was forbidden – and don’t even mention physical punishment.” 1

It should be noted that in the Soviet POW camps, the inmates were protected by international law, whereas in the ÁVH-run camps or prisons the commander of the institution was the God-like supreme ruler. In the camp of Kazincbarcika, the commander informed the inmates:

“First we will destroy you physically, then we will break your resistance, and after that we will hang you. We can do anything in this country whatever we want.” 2

The camp at Kazincbarcika operated between October 6, 1951 and September 16, 1953. After this time, the camp was dismantled and the prisoners were released; however, these “freed” men had a very difficult time finding jobs. Generally, the only type of work available was at a lower skill and education level than they were qualified to hold. They were barred from settling in any major Hungarian city (even if their family lived or had property in one of them) and they were under police observation up to 1989 – some even beyond that point.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Russians declassified numbers of government documents relating to the Hungarian revolution of 1956. These documents were published in the book titled The 1956 Hungarian Revolution: A History in Documents in 2002 by the Central European University Press. Edited by Csaba Békés, Malcolm Byrne, János M. Rainer. These documents help us to clarify some of the events that took place during and especially before fighting began.

Just how cruel and unjust the above-mentioned Rákosi-led years were in Hungary is realized in the statement made by the head of the Soviet NKVD (secret police), Lavrenti P. Beria. When the top Hungarian leaders were summoned to Moscow after the death of Stalin, on June 13th and 16th, 1953, Beria questioned Rákosi about his overzealousness in carrying out Moscow’s instructions:

“Could it be acceptable that in Hungary – a country of 9,500,000 inhabitants – prosecutions were initiated against 1,500,000 people? Administrative regulations were applied against 1,150,000 within two and a half years. These numbers show that interior and judiciary organs and the ÁVH work very badly, …” 3

Nikolai A. Bulganin, the Soviet minister of defense, brought up the unacceptable situation in the Hungarian Army in regard to disciplinary actions:

“In 1952 and in the first quarter of 1953, 460 officers and generals were discharged for political reasons. The Army was not established in 1952. Why was it necessary to discharge this many people for political reasons? If comrade Rákosi and the CC looked at these 460 people, it would become clear that some of them are our friends, our people. Thus, they turn honest people into traitors. There were 370 desertions in 1952. There were 177,000 disciplinary punishments in the army in one year and 3 months.” 4

Coming from the Soviet leaders, this is obviously very interesting to say the least. Clearly, the communists in Hungary carried out Moscow’s instructions. But Rákosi was overzealous – either by nature or fear – and routinely overdid what was expected of him. Personally, he bears some of the responsibility for what transpired during his time in power.

New direction in the Soviet internal and foreign policy

After Stalin’s death in March 5, 1953, a very significant change took place in the Kremlin in governing style by the new leadership. First of all, the feared and “great” leader Stalin was no longer around. And so, Beria was in position to take charge since he was the head of the NKVD, the Soviet secret police; however, for some reason, he wasn’t interested in the ruthless policy of Stalin, so it seems. Without knowing them personally, it would be very difficult to analyze just what he and others were thinking at the time. Still, there was a thaw in the Kremlin that manifested itself in relationships with the satellite countries as well as in international East-West relations.

Among the top leaders of Moscow, Beria and Georgii Malenkov recognized the failure of the socialist Soviet economy. Near exclusive concentration on heavy industry for the production of military armaments worked to devastate the country in every other non-military aspect. The population of the Soviet Union paid a heavy price for the communist aim to dominate – or even conquer – the world for their kind of socialism. The living standard of the citizenry was very low, with personal freedom practically nonexistent. Beria and Malenkov sensed the unrest among the population; they launched an ambitious foreign policy to improve East-West relations. This, they hoped, would give them an opportunity to cut back on military spending; scale back heavy industry; build up light industry in order to produce more consumer goods; and raise the living standard. They felt that socialist agriculture based on collective farming also needed reform. Peasants, they believed, should be given the choice to work in the collectives or start out on their own as independent farmers if they find the ambition and ability within themselves to do so. Beria believed that people with skills and inborn ability should be put into leadership roles and should be given the freedom to carry out their job as they see fit (i.e., only the final results are important). Additionally, senseless political pressure against the innocent populace, which was responsible for filling up Soviet concentration camps, should also be curtailed or totally abandoned.

So, the top Hungarian leaders – Mátyás Rákosi, Ernő Gerő, András Hegedűs, István Hidas, Rudolf Földvári, Béla Szalai, István Dobi and Imre Nagy – were summoned to Moscow and instructed to follow the Kremlin’s lead. In a meeting held at the Kremlin on June 13, 1953, Beria, Malenkov, Molotov, Bulganin, Mikoyan and Khruschev were present. On the 16th Kiselev and Boiko also attended.

Beria led the way with the others seemingly following in lockstep. He instructed the Hungarian communists on the new principles. He told them how the reforms should be implemented regarding industry and agriculture without weakening communism and the political power structure. He believed that Imre Nagy should be the prime minister, and since he was an economist, he should be able to carry out the reform; yet, Beria kept the Stalinist Rákosi as the first secretary of the communist party.

At issue was the size of the Hungarian Army. Malenkov castigated Rákosi saying: “We wanted you to develop the army. We (will) correct this mistake. There are 600,000 people in the army. (Comrade Rákosi: Including the reserves.) So, you carried the Soviet Union’s wishes to the extreme.” 5 Beria added his displeasure: “The development of the army was discussed with comrade Stalin. Comrade Stalin gave incorrect instruction.” 6

“Comrade Stalin gave incorrect instruction?” The uttering of such a thing was unheard of, unthinkable just a few months ago. Yet, Beria made an even more puzzling statement to Rákosi regarding the army: “Today the Red Army is still in Hungary, but it won’t be there forever.” 7

It was a remarkable time in the history of communism – when even the top leaders were exercising self-criticism. They were going about the work of recognizing their own mistakes. Although, their exercise in remorse was played out mostly amongst themselves, occasionally, it was publicly acknowledged on radio or in newspapers, too.

Imre Nagy implementing the “New Course”

The Hungarian delegation went back home, and Imre Nagy set forth his “New Course” according to Beria’s instructions. However – a mere 10 days later, on the 26th of June – Beria was arrested on a trumped-up charge. Accused of spying for the British government, he was quickly executed in December of that same year. Even in the shadow of these perilous events, Nagy wasn’t hindered by the Kremlin. Malenkov and the others (although somewhat reluctantly) were still supporting his work in carrying out the “New Course.” However, the problems between Nagy and Rákosi intensified after the removal of Beria. Not only did Malenkov’s power lack the same weight that Beria’s had, he was now alone. Nagy was a reformist; Rákosi, a Stalinist who demonstrated keen ability to liquidate those who dared to cross him. However, the change in Moscow – even without Beria – was still in place. So Rákosi, the ruthless dictator, set out to make Nagy’s life more difficult. He obstructed Nagy’s “New Course” reforms in any way he could. Aiding him were the Stalinists still deeply entrenched in the Hungarian communist party and economic sector.

After Beria was removed, Malenkov was elected prime minister. In September, Nikita Khrushchev was elected to be the first secretary of the Soviet Communist Party.

On May 5, 1954, Rákosi set up a meeting with the Soviet leadership in direct opposition of Nagy. Nevertheless, they both went to Moscow, where they were castigated in short order. Both were instructed to exercise self-criticism and recognize their mistakes. The Soviet leaders still supported Nagy (which must have angered Rákosi) as they were sent back home to Hungary. The problems continued between Nagy and Rákosi, and in January of 1955, they were ordered to return to the Kremlin for another consultation. By this time, the mood had soured towards Nagy. He was severely castigated. What angered the Soviets was Nagy’s unwillingness to offer any self-criticism or recognize his mistakes. At one point, Nagy offered his resignation as the Soviet leaders became unhinged. ‘How dare he? Who is he to decide what he wants to do and what not?’ Even Malenkov made an unfavorable remark: “Rotten movements hide behind comrade Nagy.”8 After this showing, Nagy was demoted and eventually expelled from the communist party. There may be more to Nagy’s removal than meets the eye, however. In the spring of 1955, Malenkov lost his job, too; he found himself demoted to deputy prime minister.

East-West relation

The death of Stalin directly affected the relationship of the two superpowers, as well as world politics in general. In April of 1953, Charles E. Bohlen became the United States Ambassador to Moscow; he remained in that capacity until April 1957. Through his post, Bohlen personally knew the Soviet leaders when the first great change took place in that country in the years preceding the Hungarian revolution. In 1973, after forty years of service in the diplomatic core, he wrote a book titled Witness to History: 1929-1969. Bohlen wrote about the difficulties in gathering information with which the relationship of the two countries could be based on in a secretive, closed society such as the Soviet Union. Foreign diplomats could not – or very rarely could – make friends with Soviet citizens and only for a short time because even occasional contact might jeopardize their freedom, or even their life. And so, the diplomat’s main source of information was the news media. Learning to read between the lines became a high art, along with picking up bits of information from other western diplomats. On more than one occasion, one or the other high-ranking Soviet official blurted out something newsworthy. That happened in the case of Beria’s demise.

According to some contact of Bohlen’s, Beria was disposed of because he was replacing the old Stalinists from the NKVD with his own people. The others feared him. And in turn, before he could become all-powerful like Stalin, they arrested him. This reasoning on the surface looks convincing, but Beria (as the head of the NKVD) had the power right from the beginning to eliminate his political enemies. From all accounts, he does not appear to have done this, however. Unlike in former regimes, his Stalinist ‘enemies’ were not liquidated physically – they were either demoted or removed from their positions. Other factors besides these may have also been in motion behind the scenes. The available information on Beria, however, seems to indicate that he wanted properly qualified people in charge; he appears not to have been merely interested in grabbing power. He was probably a team player just like the others. Bohlen called it the “collective dictatorship,” meaning from that point forward, the decisions in the Kremlin would be made collectively.

As we know, East-West relations at the time were quite rocky. We like to think that those bumps were all caused by the Soviets; however, a closer examination bears out that this was not always the case. For instance, in the fall of 1954, Khrushchev (like the others) supported the development of light industry in order to produce more consumer goods. But, wrote Bohlen, “By December, after plans to rearm West Germany were announced, he shifted the emphasis on development of heavy industry.” 9 This most likely was the reason for Nagy’s removal and Malenkov’s demotion. In Bohlen’s judgment, Malenkov was the most intelligent of all. The decision by the US to arm West Germany is hard to understand even today because the talks were proceeding in a good direction regarding the Soviet removal of troops from Austria. The day before the agreement was signed on May 9, 1955 West Germany became a member of NATO. On May 14th, the Soviets responded with the Warsaw Pact. Even with this escalation, the Soviet troops were withdrawn from Austria by December. The Soviets also released 9,626 German prisoners of war along with the last Hungarian POWs and politicians.

From left: Molotov, Malenkov, Peruvkin, Khrushchev, Shepilov and Bulganin, Bohlen facing them.

Rearming West Germany

Although, rearming West Germany must have bothered Khrushchev and his comrades a great deal. In his letter to the leaders of the satellite countries on July 13, 1956 he writes:

It is of utmost importance for the socialist bloc, and especially for the German Democratic Republic, that the Declaration of the two governments finds the German Democratic Republic and the German Federal Republic’s negotiations about the unification of Germany most expedient (practical, useful). It would create more favorable conditions for the democratic forces in Germany, who are fighting for peaceful and democratic unification of Germany. (A History in Documents. Page 138.)

Then, on page 139 he continues:

Comrade Tito explained that the West Germany representative informed them of their intension to form a good relationship between the German Federal Republic and Poland, and that they are prepared to concede German-Polish border revisions.

It is obvious that Khrushchev was willing to go as far as reunifying Germany for the neutrality of Germany.

Offering olive branch to the Yugoslav dictator

Other significant events took place in 1955 that also deserve mention, including the fact the decision by the Soviets to bring Yugoslavia back into their camp. In 1948, the Yugoslav dictator, Tito, broke away from Moscow. With help from the West, he’d begun building his own kind of socialism. This move by the Kremlin to bring Yugoslavia back into the fold affected Hungary, too – especially Rákosi. When Tito broke away from Stalin’s “fatherly love,” in the eyes of the Soviet camp he became America’s “dog on leash.” As far as the international communists were concerned, Tito was a traitor – a traitor who had other collaborators like László Rajk, whom was Rákosi’s internal minister. In 1949, Rajk and some others were singled out for “spying” for Tito. They were arrested for espionage and later in that same year swiftly executed. Rákosi personally directed the preparation of the charges against Rajk, and bragged about it publicly. Tito, of course, didn’t take these events lightly. Consequently, when the Soviet Union offered an olive branch to Tito, Rákosi found himself in the hot seat, forcing him to bend over backwards to please the Yugoslav dictator. Eventually, Hungary was forced to pay $85 million reparations to Yugoslavia.10

The new Soviet policy came into bloom by the Summer of 1956

So it is that we arrive in great leaps and bounds to 1956, which started out with a big bang. From February 14-25th, the Soviet Communist Party held its XX Congress. Shrouded in complete secrecy, only high-ranking party officials were invited, including those from the satellite countries. However, just like Bohlen wrote in his book, some participants dropped a telling public remark here and there. Anastas I. Mikoyan, member of the Soviet Politburo, offered the opening shot in a speech on Stalin’s mistakes and on the cult that he surrounded himself with. When Khrushchev delivered a speech shortly before the conclusion of the Congress, he went a lot further than Mikoyan ever did – castigating Stalin as well. He did admit, however, that for some criminal acts they themselves were also responsible. One example: the purge of 1937. In that year, approximately 750,000 communists fell victim to the ruthless system in place; Khrushchev said they must ask for the forgiveness of their comrades for this deed. They would release some of the political prisoners – mostly communist – who were interned on trumped up charges. The truth-telling and forgiving had its limits, of course. Khrushchev did not mention the six million Ukrainians or three million in the Don-valley who were deliberately starved in 1932 and 1933. Even so, it was still a significant admission. (The speech was published 30 years later in 1996.) It had to be a jolt to the Stalinists in the Soviet Union as well as to the delegates from the satellites. Although this was good news to Nagy and his followers, chills were likely running down the collective spine of the Hungarian Stalinist leaders. It was this congress that gave birth to the idea of a “peaceful coexistence” between the East and West.

In that spring and summer of 1956, barbwire fences and minefields were removed from the Hungarian-Yugoslav border. Later that year, the same was done on the Hungarian-Austrian border, indicating the gradual improvement in East-West relations. As time passed on, in Hungary proper, the Irodalmi Újság (the newspaper of the Writers Union) contained ever-bolder articles criticizing the general conditions – and even the communist party itself. It’s important to remember that these writers were all communists; but, not necessarily Stalinists or pro-Soviet. A new communist writer’s group, the Petőfi Circle, was formed, its members intent on reforming the party. They wished perhaps to getrid of the Stalinists, but they were intent on keeping the system. They held their first important meeting on the 17th of March. To this meeting, they invited the former leaders of the banned MEFESZ (Association of Hungarian University and College Unions). Budapest hearts were stirring, and the meeting of June 27th found 5000-6000 participants. There were people in the audience who raised issues that had been taboo for ten years. They openly discussed the occupying Soviet forces in Hungary and the 1920 and 194711 peace treaties – commonly known as Treaty of Versailles and Paris – which followed the first and second World Wars (Hungary was dismembered and had lost 2/3 of her territory and population as a result). The widow of Rajk, Júlia, declared that Rákosi not only killed her husband, but also separated her from her young child.12 This openness could not stand, and the Central Committee of the Hungarian Workers (Communist) Party on June 30 banned the Petőfi Circle. The Writers Union openly protested the CC’s action – something that never could have occurred when Stalin was at the helm.

The Soviet leaders understandably sensed the worsening situation in Hungary, and on the insistence of Tito, they replaced Rákosi with Ernő Gerő as the first secretary of the communist party. András Hegedűs remained as prime minister. Unfortunately, these moves did nothing to solve the problems as far as the Hungarian public was concerned; in fact, the moves added further fuel to the fire, as both appointees were Stalinists. Rákosi stepped down, citing his health as the reason for his “resignation”.

Incredible events began to unfold at lighting speed. Early in September, the Presidential Council pardoned 50 social democrats. In the middle of the month, the Writers Union demonstrated in support of Imre Nagy. On the same day, the Petőfi Circle resumed organizing public meetings again. On October 4th, high ranking ÁVH officers were arrested.13 On the 6th, László Rajk’s reburial took place with some 200,000 people participating. The Szabad Nép (the communist newspaper) published an article on the first page titled “Never Again,” meaning that no communist should be executed again. On the 12th, a long time high ranking party official, Mihály Farkas, was singled out to pay for all the ills and was arrested. On the following day, Imre Nagy was reinstated into the communist party. Three days later, on the 16th, some 1600 students from the University of Szeged reestablished the formerly banned Association of Hungarian University and College Unions (MEFESZ), which was independent of the communist party or the DISZ (Association of the Workers – communist – Youth.) On October 19th, all of the Soviet occupation forces in Hungary were alerted and placed in a state of readiness. The same day, the MEFESZ sent their delegates to all universities and colleges to organize and formulate their demands. On the 22nd of October, a large assembly of students from across Hungary convened at the Technical University in Budapest, where they drafted the first version of demands in  16 points. On the 23rd, the Szabad Nép ran an article on the first page titled the “New Spring Parade.” These are just a few of the many breathtaking things that occurred during those heady days; the reader most certainly notes the acceleration of events taking place.

16 points. On the 23rd, the Szabad Nép ran an article on the first page titled the “New Spring Parade.” These are just a few of the many breathtaking things that occurred during those heady days; the reader most certainly notes the acceleration of events taking place.

← Demonstrators gather at the statue of the Polish General Joseph Bem

On the 23rd of October, around 11 AM, people demonstrated in Debrecen, a large city near the eastern Hungarian border. 12:53 PM, Radio Kossuth in Budapest announced the ban on all demonstrations. An hour and a half later, the authorities revoked the ban. Obviously, they were quickly losing control. Around 3:00 PM, a large group of demonstrators congregated in front of the Statue of Petőfi – one of the most loved Hungarian poets from the 19th century. They then marched to the statue of Bem – a Polish general who fought for Hungarian independence in 1848-49 – where they showed their solidarity to the Polish people struggling under the grip of communism as well. Around 5:00 PM, a crowd of 200,000 strong gathered in front of the Capitol Building, at Kossuth Lajos – the leader of the 1848-49 war of independence – Square. By this time, people of all walks of life had joined the student protestors. Large groups of people were gathering in front of the Radio Station where the students and other protestors wanted their 16 point demands to be read on the radio. They were denied. The crowd swelled, and the authorities answered by reinforcing the guards (whom were also members of the hated ÁVH). It was in Debrecen – not Budapest – where the first shots in the Hungarian revolution were fired at 6:00 PM. Three deaths were recorded and scores of wounded. As the events spiraled out of control, Gerő, the first secretary of the communist party, requested help from the Soviet Union. At 9:00 PM, Imre Nagy addressed the crowd at Kossuth Square from the balcony of the Capitol Building. But he made the mistake of calling the demonstrators “elvtársak” (comrades). This didn’t go over well at all. Jeers and boos were the response. With a newfound strength in numbers, Hungarians now wished the communists, the Soviets, and even Nagy to return to Moscow. By the evening, it seemed that all the citizens of Budapest were on the streets. At 9:30 PM, people demolished the statue of Stalin, who was one of the most ruthless tyrants who’d ever lived and ruled over them. (According to the latest estimates, Stalin was responsible for the loss of 40 million lives throughout his ruling domain.) The first shot to be heard at the Radio Station was fired by the ÁVH around 8:30 PM. All hell broke loose. The demonstrators now became revolutionaries. People armed themselves with weapons procured by soldiers and police; even more firearms were available from the Budapest Lámpagyár, “Lamp factory”. It was common knowledge that the “lamp factory” was always in reality a weapons factory under heavy guard by the ÁVH . Yet, curiously, on the evening of the 23rd, an unarmed old man guarded the facility. Any number of curious events lead many to believe there were provocateurs working behind the scenes to foment a revolution. Could it be possible that the Stalinists in the Soviet NKVD and the Hungarian ÁVH had a vested interest in torpedoing the reform movement in order to save their own hide and keep the Soviet troops in Hungary? At the Radio Station the battle went on until dawn the next morning, when the rebels overtook the building.

Someone tore the communist insignia from the Hungarian flag

Bottom: Soviet style insignia before the revolution. Top: insignia after the revolution

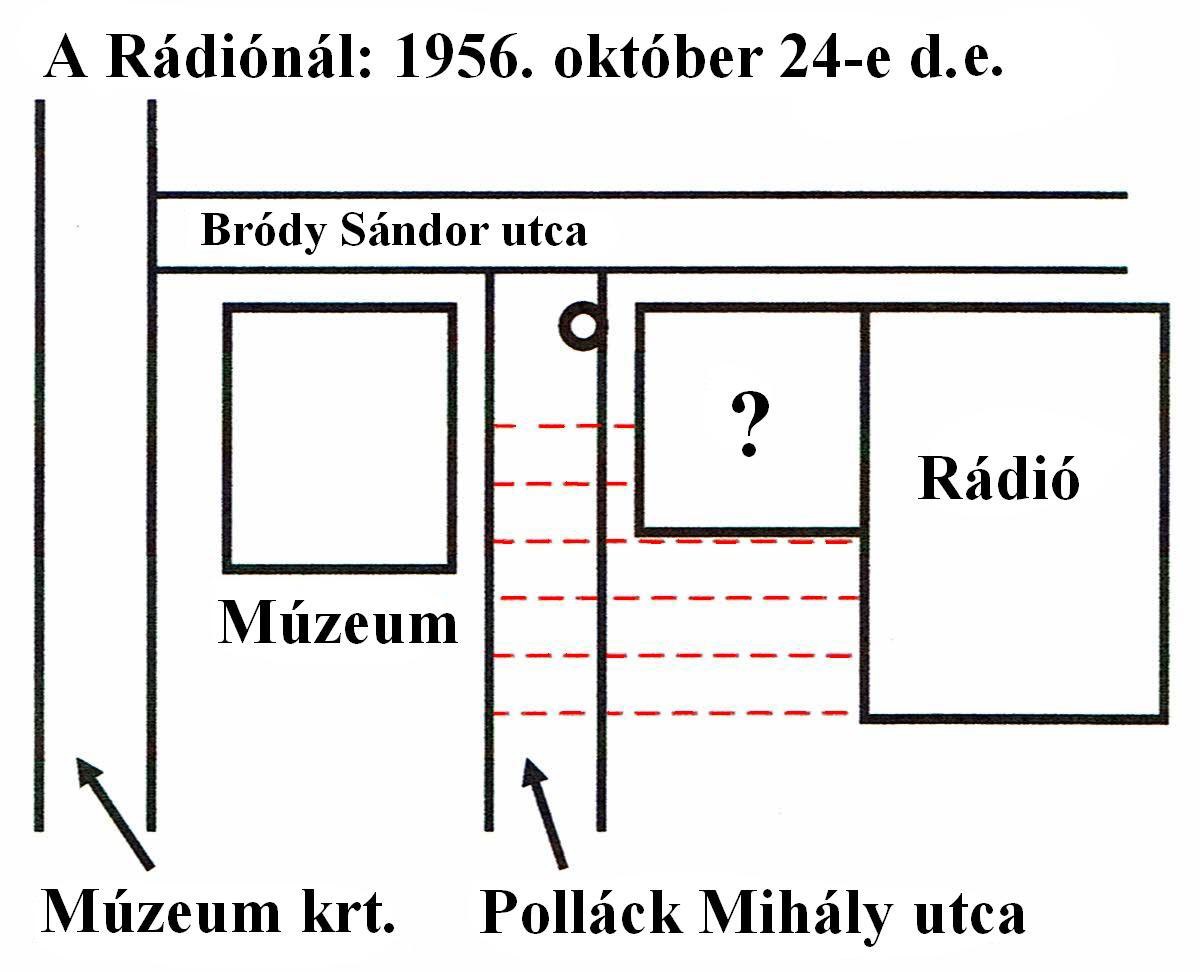

Massacre at the Radio Station

Radio Station: The broken red lines indicating the dead bodies

A personal reflection

On the morning of October 24th, I was getting ready for work at the usual time. I heard some unusual noises from outside, which sounded like gunshots. The streets were filled with people, a sight like I had never seen before. I was told that a revolution is going on; no one is going to work; public transportation had been halted in the entire city. So, I walked to the nearest square where I found a truck being loaded. The driver said he is carrying people into the center of the city where the fighting is still in progress. As I look back decades later, it was kind of odd. Blood and brain tissue were splattered on the floorboards of the truck. That startled me for a second, but I understood that these were serious times, revolutionary times, where some would die. I got on the truck, which dropped me off near Calvin Square in the downtown area of Budapest. I saw a dead Hungarian soldier lying on the sidewalk, an automatic weapon beside him. I picked up this gun and started to walk toward the sound of gunfire. It turned out to be the Radio Station. At that time there was an empty lot behind the building (?) next to the Radio Station; it was covered with dead people, civilians and soldiers alike. The bodies lying side by side like matchsticks. I would estimate they numbered around two hundred. No guns were beside them. They could not have died at the spot where they were laying. The dead bodies were moved from somewhere, but from where? We know that the Bródy Sándor street – front of the Radio Station – were filled with many thousands of demonstrators the night before. Some of the people demanded that they should be allowed to air what the people want. Of course, they were denied. Eventually the ÁVH fired into the crowd in order to disperse them. If there were 200 dead, there had to have been twice as many wounded. To have so many causalities, the ÁVH must have blasted the demonstrators with heavy machinegun fire. Next morning, the first responders evacuated the wounded, and they moved the dead bodies from Bródy Sándor street to this empty lot and the narrow Pollák Mihály street. I walked through this street stepping over the bodies. It didn’t occur to me then that I could have been shot down like a rabbit. The sound of the gunshots came from the front of the building, and when I got there the last of the six ÁVH men who had been protecting the building surrendered. This was around 10:00 AM; they had probably hidden in the building overnight, or they came back after the revolutionaries left at early morning. Some in the crowd wanted to execute them; others thought it should be left up to the law. They were taken away. I don’t know what happened to them.

Soviet armored units ordered into Budapest

Finally, Soviet armored units from Székesfehérvár were ordered into Budapest. They reached the city limits sometime around 3:00-4:00 AM on the 24th. When the Soviet troops fired their first shot, the revolutionaries had become freedom fighters, because the occupation force had involved itself in Hungarian internal affairs. It took some time for the top Soviet leadership to realize that they made a grave mistake. First, they didn’t recognize the deep-seated resentment and desperation of the Hungarian people. They disregarded Hungarian valor of which there are plenty of examples in Hungarian history. They didn’t figure on Hungarian resourcefulness either. The Soviet officials mistakenly believed that once Soviet tanks appeared on the streets of Budapest and other major cities that the would-be freedom fighters would simply disappear. It was not to be.

Another surprise was waiting for the leaders of the Kremlin. Several views have been conjectured as to what caused the fall and dismemberment of the Soviet Union, and a few good reasons could be sighted; however, the most important has never even been mentioned. The decline of the Soviet Union started with the occupation of Eastern Central-Europe at the end of the Second World War. That was the first time that Soviet soldiers and civilians by the millions realized they were not living in the supreme earthly paradise they’d been indoctrinated to believe in by their Marxist-Leninist classes. Occupation forces serving for years in Hungary, for example, became very friendly with the locals and had a good life. When they were given the order to fire upon the friends they’d made over the years, they found it a very tough thing to do. Stories in the aftermath revealed  that there were times political officers held pistols to their backs to force them to fire their guns.

that there were times political officers held pistols to their backs to force them to fire their guns.

← On the 24th there were more demonstrations, however, the battle scars are evident on the streets .

That said, the contribution of these Hungarian-friendly Soviet troops takes nothing away from the heroism and resourcefulness of the country’s native freedom fighters. Large numbers of heavy fighter groups developed throughout Budapest without any organized central leadership. Each one of these independent centers developed their own tactics, fighting with great efficiency. The Soviets, ironically, were to become intimately acquainted with the effectiveness of the Molotov-cocktail as Hungarian freedom fighters captured tanks, anti-tank guns, ammunitions and many other weapons using this crude device. One of the most organized and successful fighter groups to be found operated in Corvin köz (Corvin Passage), the site which become a key battleground for the fight for liberty. According to group leader Gergely Pongrátz, elected as the newly-free nation’s commander in chief on October 30th, the heaviest fighting occurred on the 26th. On that late October day, the fighter group destroyed 17 Soviet tanks.14 The USSR began sending more fresh troops into Hungary who were less sympathetic to the plight of the people. Then, mere days into the uprising, on October 28th, a cease-fire was declared. The Soviets, announcing their withdrawal from Budapest, had by then lost about 100 tanks and suffered casualties of 600 dead and many  more wounded. The Hungarian freedom fighters also suffered heavy casualties.

more wounded. The Hungarian freedom fighters also suffered heavy casualties.

← Destroyed tank and building on the streets of Budapest

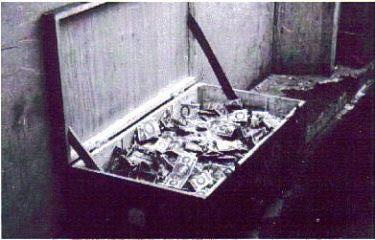

The destruction was massive. Barricades and burned out tanks and buildings lay in the fighting’s wake. Smashed display windows with valuable merchandise for the taking, but no one touched them. To help families that had lost the sole breadwinner, the Hungarian Writer’s Union placed a large wooden box on one of the city’s main street corners seeking donations. No one guarded it as it filled up with money. Materialistic considerations were not the inspiration of this fight. Achieving freedom and independence for Hungary was the prevailing aim.

The bloodbath at Kossuth Square

Thanks to Edit Kéri’s diligent research, today we know that Antal Apró (the member of the Communist Party’s Central Committee) requested and received permission to do whatever was needed to scare the people into stopping their demonstrations. Apró teamed up with Ivan Serov (the head of the Soviet KGB) and together they crafted a sinister and deceptive plan. On the 25th of October, five Soviet tanks were ordered to go to Kossuth Square, located behind the Parliament Building. Emerging somewhat mysteriously from five different sections of the city at roughly the same time, the slow-moving tanks stopped along the way to fraternize with the people. People climbed on top of these tanks, waving the Hungarian flag. Others unable to secure a spot conveniently hitched a ride on magically appearing trucks ready to whisk them to the Square.

According to some estimates, 10,000 people convened on the Square singing the national anthem. Suddenly, from the top of the Agriculture Ministry Building, snipers opened fire on the masses. Soviet tank soldiers also did not know what was going on and fired into the crowd. The result? About 1,000 dead and probably twice as many wounded.

Eyewitnesses recall people stationed on top of the building wearing uniforms with a green shoulder patch: the insignia of the Hungarian Border Guard. Understandably, witnesses on the scene assumed they were members of the Border Guard who’d committed the atrocities. This is very unlikely and was probably another element of their deception. The communists, relying on and entrusting the ÁVH to deflect the blame from the sadistic bunch, likely donned the uniform of the Border Guard.

It is worth noting that Apró’s granddaughter, Klára Dobrev, is a representative in the European Parliament and wife of Ferenc Gyurcsány, prime minister of Hungary from 2004 to 2009. After destroying and looting the  Hungarian economy, as of today (2019) Gyurcsány is sill a member of the Hungarian Parliament. What a “democracy”!?

Hungarian economy, as of today (2019) Gyurcsány is sill a member of the Hungarian Parliament. What a “democracy”!?

← Bread is distributed from the trucks to the hungry citizens

Scores of other cities reported clashes with soviet troops, and more so with the ÁVH. Debrecen, Miskolc, Kecskemét, Székesfehérvár, Esztergom, Mosonmagyaróvár, Zalaegerszeg, Nagykanizsa and others all rose up to do what they could to secure a better future.

While the fighting went on, the nation’s beleaguered farmers brought food to the city. Was this their contribution or did the government order it? International aid, mainly medicine, also was shipped in by airplane. The first  flight arrived from Warsaw on the 26th attesting yet again to the close relationship between the Poles and Hungarians that had existed over many centuries.

flight arrived from Warsaw on the 26th attesting yet again to the close relationship between the Poles and Hungarians that had existed over many centuries.

← In a large wooden box, donations are collected for the relatives of the fallen

The fighting, however, was far from over. The ÁVH still held out in several places in Budapest. One area where the severest fighting took place was at Köztársaság tér (Republic Square) on October 30th. As already noted, The ÁVH was known for their cruelty; they thought nothing of killing members of the rescue team coming to the aid of the wounded in the streets. The ÁVH captured at Republic Square would find itself on the receiving end of one of the few occasions where the crowd lost its temper and lynched the leaders of the hated group.

Square would find itself on the receiving end of one of the few occasions where the crowd lost its temper and lynched the leaders of the hated group.

← In white, the gunned-down member of the rescue team

On October 30th, Hungarian soldiers and freedom fighters rescued Cardinal Mindszenty (who’d been arrested in 1948 on trumped-up charges and jailed at Rétság). The next day, a convoy of cars brought the cardinal to Budapest. People on both sides of the road lined up by the thousands as church bells rang jubilantly. In solidarity, Pope Pius XII sent a telegram to the tortured high priest.

Acting as Prime Minister again, Imre Nagy recommended talks be held between the government and the freedom fighters. Commencing at 8:00 PM on the evening of the 29th in the Defense Ministry building, both the freedom fighters and high-ranking military officers took part in the negotiation. Each group of the freedom fighters sent their own delegates to these talks. From Corvin Passage, Ödön Pongrátz (the brother of Gergely Pongrátz) and Dr. Sándor Antalóczi (a young doctor who went by the name “Doki”) were present. An engineer, József Dudás, rose up to demand the removal of a Stalinist from a position of leadership (he was executed in January 1957). General Gyula Váradi chaired the meeting. His intention was to acquire a written and signed declaration from the freedom fighters to lay down their arms15 because the demands of the people had already been fulfilled – so he said. Ödön Pongrátz stopped this idea in its tracks, saying that he knows of no other revolution where the victors laid down their arms. The freedom fighters made it clear to the officers in attendance that they will not lay down their arms if Soviet troops remained on Hungarian soil. Thus, the Nagy government was forced to take up negotiations with the Soviet Union on the removal of their troops from Hungary. By a subsequent meeting held on the 31st of October, an agreement was reached to set up a new National Guard in which the freedom fighters would be represented.

Near Corvin Passage was the Kilián military barracks. The commander of Kilián was Captain Lajos Csiba. Home on the night of the 23rd, he received a call from the barracks that rebels were trying to break in. By the time he was able to reach the barracks, the main gate was busted open and the revolutionaries had made their way inside and were demanding guns. They had very few guns stored at the barracks, so Csiba requisitioned some from his higher-ups; none were delivered. Because Kossuth Radio had begun the constant airing of the government’s demand that the rebels lay down their arms, Csiba thought that he could capture and disarm some of them in order to bring about order. He needed their guns anyway because, at this point, bad blood developed between Kilián and the freedom fighters of Corvin Passage. During the most intense fighting on October 25th, Colonel Pál Maléter (Csiba’s superior officer) showed up at the barracks with five tanks and set one up in front of the main gates of Kilián. In his Napló (Journal), Csiba stated: „In the evening and night we exchanged gunfights with the rebels. At the main gate, Captain Szabó and first-lieutenant Kolmann and a soldier had been wounded; we took them to the hospital.” 16 The hostility didn’t stop between the Kilián and Corvin factions until the ceasefire was announced on Kossuth Radio on the 28th. Csiba mused, “…they called the rebels armed patriots. This was the time when we found out that we fought against armed patriots.” 17

October 29th was a nice fall day. I went out for a walk in Népliget, a large park within the city of Budapest. The western side of Népliget borders on one side of Üllői Road, and the Kilián barracks is located on the other side. I noticed a large group of demonstrators on Üllői marching towards downtown and chanting: “Ruszkik haza!” (Russians go home). “Nagy Imrét a kormányba!” (Imre Nagy installed in government.) When we reached Kilián, the crowd stopped. Somebody in front chanted: “Maléter the heroic defender of Kilián!” “Maléter into the government!” The crowd repeated the chant, me included. Decades passed by the time I realized that the communists intending to get popular support for their man probably organized this demonstration. Maléter’s star was like a comet, reaching its zenith on the 3rd of November when Nagy made him a General and the Minister of Defense. That evening, Maléter and three others – General Miklós Szűcs, General István Kovács, and a communist politician Ferenc Erdei – took off to Tököl (the soviet military headquarters in Hungary) to finalize the details of Soviet troop withdrawals. They were all arrested.

The night before, on November 2nd, the same people and Csiba had dinner at the Kilián barracks. Pongrátz quotes General Szűcs from his Memoirs stating that Maléter made the following statement: “I’m a believer of socialism, I didn’t shoot, and I’m unwilling to shoot, or order to shoot on the soviet troops, because I can thank them for my life and career.” 18 Maléter was warned that the Soviets might arrest them, but these officers – one hundred percent loyal to the Soviets and communism – either could not or would not contemplate that possibility. What makes this whole Maléter story unique is that he has been promoted as hero of the Hungarian revolution, when in fact he was on the Soviet side from start-to-finish. No matter, the communists executed Maléter along with Nagy in 1958. During a very difficult time, they were both communists to the end. Both hoped to save the communist system rather than cut ties with it. Nagy for example, could have elevated Colonel András Márton to the post of Defense Minister. Refusing an order to launch an attack against Corvin Passsage with 400 officers, Márton personally went to the freedom fighters to offer them any assistance they needed to carry on the fight. The execution of Nagy and Maléter by the communists stands as yet another example of how that ruthless system actually worked.

As is the case with most major events in history, decades tick by before light is cast on what happened behind the closed doors of the all-powerful. Telling information has recently eked out regarding the Hungarian revolution, most especially on the bloody demise of it.

The Hungarian revolution broke out during a time when the American presidential and congressional campaign season was rolling into its final stretch. President Dwight D. Eisenhower insisted that Secretary of State John Foster Dulles insert the following statement in his campaign speech delivered at Dallas, Texas on October 27th: “… the American leadership does not regard the Eastern European states potential military allies of the United States.” 19 This remark was made the very day after Hungarian freedom fighters achieved their most significant victory over Soviet forces. On October 28th, Henry Cabot Lodge, America’s ambassador to the United Nations, “… quoted the relevant passages from Dulles’ speech during a session of the Security Council.”20 Was America delivering an unmistakable message to the Soviets of her “neutrality?”

Charles Bohlen, the United States ambassador to the Soviet Union from April 1953 to April 1957, served at a very critical time when great change was taking place in Moscow (he also personally knew key Soviet leaders even before he became ambassador). In 1973, he published the book Witness to History, offering his account of 40 years in the diplomatic service. One chapter is devoted to the Hungarian revolution, and the following passage from it is noteworthy to explore:

“Quite a few big black Zis limousines were seen entering the Kremlin on October 29th, indicating that the full Presidium was meeting or had met, and officials were being instructed on carrying out the plans. I had just received a cable from Dulles, who urgently wanted to get the message to the Soviet leaders that the United States did not look on Hungary or any of the Soviet satellites as potential military allies. The cable quoted a paragraph from Dulles speech at Dallas to that effect, and emphasized that it had been written after intensive consideration at the “highest level” – an obvious reference to President Eisenhower.” 21

Bohlen continued:

“I was able to convey the message to Khrushchev, Bulganin and Zhukov at the receptions that afternoon in honor of Turkey’s National Day and at the Afghan Embassy.” 22

According to Bohlen, the message was delivered on the afternoon of the very same day. The ambassador recalled that “the American assurance carried no weight with the Kremlin leaders. They made up their minds to crush the revolution …” Interesting, but there is a discrepancy if one compares it to the since-released confidential minutes of the Central Committee meetings of the Soviet Communist Party.

The Soviet Central Committee most likely met daily while the fighting went on in Hungary, and a very important decision was made on the afternoon of October 30th. The following leaders were present: Bulganin, Vorosilov, Molotov, Kaganovich, Saburov, Brezsnyev, Zsukov, Sepilov, Svermyk, Furtseva and Pospelov. Khrushchev joined them a little later (he was meeting with Chinese delegates opposing the pullout from Hungary).

At the beginning of the meeting, a letter was read from Hungary in which Mikoyan and Suslov informed the leaders of the devolving situation. It was getting worse by the hour, they wrote. Remarks from the minutes:

Zhukov: (Touched on some other relating issues, then said.) “Nagy is playing a double game (in Malinin’s opinion). Comrade Konev is to be sent to Budapest.”

Khrushchev: (At this point Khrushchev stepped in, and informs the others of the agreement that was reached with the Chinese. They agreed to the plan to remove the troops from Hungary. Then he said): “We should adopt a declaration today on the withdrawal of troops from the countries of people’s democracy (and consider these matters at a session of the Warsaw Pact), taking account of the views of the countries in which our troops are based.”

Molotov: “Today an appeal must be written to the Hungarian people so that they promptly enter into negotiations about the withdrawals of troops.”

Voroshilov: “We must look ahead. Declarations must be composed so that we aren’t placed into an onerous position. We must criticize ourselves – but justly.”

Shepilov: “There is no need for an appeal to the Hungarians. We support the principles of non-interference. With the agreement of the government of Hungary, we are ready to withdraw troops.”

Zhukov: “We should withdraw troops from Budapest and, if necessary, withdraw from Hungary as a whole.”

Furtseva: “We should adopt a general declaration, not an appeal to the Hungarians.”

Saburov: Agrees about the need for a Declaration and withdrawal of troops. “It’s impossible to lead against the will of the people.”

Khrushchev: “We are unanimous. As a first step, we will issue a Declaration.”

Khrushchev: “There are two paths. A military path – one of occupation. A peaceful path – the withdrawal of troops, negotiations.”

Molotov: “We should clarify our relationship with the new government. We are entering into negotiations about the withdrawal of troops.”

The Declaration was written in accordance with the above statements and sent out to respective governments. It was also published in Pravda on October 31st, indicating that the Hungarian matter will be solved peacefully. In Hungary, the newspaper Függetlenség translated the Declaration without delay and published it on the 31st. At this point, it appeared that the Hungarian revolution was won. From these documents one can glean that, if the US would have recognized the Nagy government diplomatically, the Soviets would have pulled their military out of Hungary. Besides the success of the revolutionaries, what forced the Soviet leaders to make this initial decision to withdraw their troops? Most likely, it was the previously touched upon friendship that had developed over the years between the Soviet occupation forces – at even high levels of command – and the Hungarian people. Emil Csonka in his book A forradalom oknyomozó tanúi (Witnesses for the Researchers of Revolution) writes that several high-ranking Soviet officers worked out truces with Hungarian officials in the countryside. He cites one case from Győr where Colonel Schwarz made a radio announcement stating: “I believe that the Hungarian people have the right to rise up against their oppressive leaders.” 23 Not only did high numbers of soldiers and officers join the Hungarians in actual combat nationwide, they also supplied or sold weapons, ammunitions and even gas to them. Some of that fuel had been used quite successfully for Molotov-cocktails. The clear victory gained by the freedom fighters, and the resulting decisions made at the top tier of Soviet leadership should have been enough to ensure the liberty of the Hungarian people. At this point, the United States should have diplomatically recognized the Nagy government and the Soviets would have pulled their military out of Hungary.

Returning to the cable message that Mr. Bohlen had received and delivered to the leaders of the Kremlin, according to the ambassador, the communist leaders had already “made up their minds.” And so, the question is: Why would the Soviets write a cumbersome Declaration indicating that they were willing to negotiate and withdraw their troops from Hungary on the following day? Why would they publish it in Pravda on the 31st? It is unlikely that they wrote the Declaration for the purpose of deception only; they just as effectively could have used diplomatic channels and the media for that purpose, a tactic used already in previous days. Perhaps Mr. Bohlen’s memory of events had faded somewhat by the time he wrote his book. Or could he purposefully have mischaracterized what truly happened? Obviously, it’s difficult to imagine that when Bohlen read the Declaration in Pravda on the morning of the 31st, that he would not remember it clearly in the future. He likely found it astonishing; after all, it wasn’t an ordinary Declaration – and it certainly wasn’t an ordinary day. Bohlen, however, and perhaps suspiciously, doesn’t even mention the Declaration in his book. From the evidence we now have at our disposal, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to suggest that Mr. Bohlen himself was the one who informed the State Department of the Declaration’s contents. One can only wonder: If the Soviet leaders unanimously agreed to solve the Hungarian matter peacefully on the 30th, what changed their minds a mere 18 hours later, on the 31st, to crush the revolution? Would it be ludicrous to suggest that the reception at the Afghan Embassy was in the afternoon of October 31st, instead of the 29th? Or the cable itself was sent on the 31st? Could it be that the Soviet leaders received assurances delivered personally by a representative from the United States that it would not meddle, which ultimately changed their minds as to the course they could take to solve the Hungarian situation? Why was it even necessary to send such a message?

There were other noteworthy events in those crucial days of revolution. For example, on October 31st, President Dwight D. Eisenhower in his radio and television address “assures the Soviet Union that the Unites States does not view either the new Polish or the new Hungarian leadership as potential allies.” 24

Well now! So, as Comrade Molotov wished to clarify the “relationship with the new government” of Imre Nagy, Mr. Eisenhower didn’t see the “new Hungarian leadership as a potential ally.” This was made clear to the Soviets by Secretary of State Dulles on October 27th and reaffirmed by Ambassador Lodge on the 28th at the UN. And what of the “new Polish leadership?” On October 19th, Mr. Wladyslaw Gomulka was elected to be the first secretary of the Polish Communist Party. Like Nagy, he was jailed during Stalin’s era. Gomulka began removing some of the Stalinists from the Party and was working to gain more independence from the Soviet Union. Evidently, this didn’t go over very well with President Eisenhower. So, if it wasn’t the telegram that changed the minds of the Soviet leaders, then what was it?

Some people believe that the Suez-crisis offers a possible explanation. While it could not be completely ruled out, however, the British-French and Israeli joint operation started on the 29th of October with the Israeli attack on Egypt. A few months earlier, Egypt nationalized the Suez Canal (which was under British control), so they wanted to reestablish that authority. The Soviet decision to solve the Hungarian issue through negotiations was made on the afternoon of the 30th. Gazing at it through this timeline, it’s very unlikely that this crisis had anything to do with the Soviet change-of-heart. Khrushchev even remarked at their meeting on the 28th, “[t]he English and French are in a real mess in Egypt. We shouldn’t get caught in the same company.” 25 Evidently, he already had information of the coming attack.

One possible explanation might be found in the smoke-filled room of the almighty powerbrokers. W. Cleon Skousen in his book titled The Naked Capitalist writes:

“Dr. Dodd said she first became aware of some mysterious super-leadership right after World War II when the U.S. Communist Party had difficulty getting instructions from Moscow on several vital matters requiring immediate attention. The American Communist hierarchy was told that any time they had an emergency of this kind they should contact any one of three designated persons at the Waldorf Towers. Dr. Dodd noted that whenever the Party obtained instructions from any of these three men, Moscow always ratified them.

What puzzled Dr. Dodd was the fact that not one of these three contacts was a Russian. Nor were any of them Communists. In fact, all three were extremely wealthy American capitalists!”

Dr. Bella Dodd was a former member of the National Committee of the U.S. Communist Party. Mr. Skousen served 16 years in the FBI, 4 years as Chief of Police in Salt Lake City. He was also the Editorial Director of the police magazine, Law and Order, for ten years and a university professor for seven.

Could it be possible that the above statement had something to do with the hard-to-explain statements and decisions of President Eisenhower at a time when the two superpowers were supposedly arch enemies? Shouldn’t America have taken advantage of the possibilities the Hungarian revolution presented? Apparently not!

Yet, there is another aspect of the actions and attitudes of the United States regarding the Hungarian revolution. At one of his news conferences, Mr. Eisenhower made another interesting statement: “The United States does not now and never has advocated open rebellion by an undefended populace against force over which they could not possibly prevail.”

Oh! Yeah?! – as any casual American might say. Not advocate open rebellion? Doesn’t this sound like what Pilate had done two thousand years ago? And what of the American Revolution’s patriots and their open rebellion against the mighty British Empire?

Two American reporters, Ted Koppel and Peter Jennings of the American Broadcasting Corporation, put together a presentation in 1985 on the Cold War. It was a sort of situation analysis of the two superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union. Among many issues explored, they touched upon the East German, Polish and Hungarian revolutions. They interviewed Richard M. Nixon (the vice president at the time of the Hungarian revolution) who said in 1985:

“It was a tragedy and a tragedy to which we contributed. We contributed to it because some of our programs that were carried on radio in Hungary called for the Hungarian people to rise up. I think many of them got the impression that we would come to their assistance. It was a terribly difficult decision for Eisenhower not to do so. But he looked at the situation and the situation was that the Soviet Union had overwhelming conventional superiority in the area. So what is our answer to Hungary, to bomb Moscow?

Eisenhower had to make that decision and decided that it would not be credible for him to threaten do so.”

On the 31st of October, the Soviet Central Committee met again. Khrushchev announced an abrupt change in plans. Saburov alone held out for the peaceful solution they’d earlier all agreed to. Marshall Zhukov ordered his armies, tanks by the thousands, to cross the Hungarian border. They were fresh forces, many of them from Siberia and Mongolia, and they had been told that they were at Suez. By the nightfall of November 3rd, they encircled Budapest and all the airports and major strategic points in the country. A day earlier, on November 2nd, the State Department sent another cable to Tito, the Yugoslavian dictator. It read in part: “The government of the Unites States does not look with favor upon governments unfriendly to the Soviet Union on the border of the Soviet Union.” 26 Could it be that the United States wanted to offer assurances to the Soviets that the first cable on October 29th (or on the 31st) wasn’t a mistake? On November 4th, early Sunday morning, the sound of heavy artillery bombardment awakened the citizens of Budapest. Heavy fighting went on for 4-5 days then  subsided, and eventually the revolution was crushed. The estimated number of people killed in action is placed officially at around 2,600, but it is probably much higher than that. Soviet losses were heavy as well.

subsided, and eventually the revolution was crushed. The estimated number of people killed in action is placed officially at around 2,600, but it is probably much higher than that. Soviet losses were heavy as well.

← The victory walks of the soviet general

In the fallout, János Kádár was installed by the Soviets as the all-powerful first secretary; he remained in that post until 1988. Interestingly enough, under Stalin’s rule, Kádár himself was jailed and severely tortured. Yet, under his rule heavy punishments were meted out. The exact number of people executed or placed into a variety of prison systems to this day is not known. The system made sure these people were disappeared without a trace. According to the best estimates available, at least 356 were executed; 341 of these confirmed. Teenagers who had fought in the revolution were executed on their 18th birthday, the last one meeting their fate in the summer of 1961. Charges were raised against 35,000 people; 26,000 of them were litigated with 22,000 being sentenced. In addition, 13,000 were interned into forced labor camps. 200,000 people escaped to the West during the months following the revolution. In total, it was a huge loss for a nation of 9,500,000 people. The reform movement was also broken, never to return in its original form.

In memory of the freedom fighters, the “pesti srác,” we bow our heads in sorrow and in pride! They wrote their name into Hungarian History with their own blood.

Mid November a notice come from the factory that all workers should report to work. So, the factory leadership set the date when production should resume. A young man stood up and firmly declared that we should remain on strike as long as the Soviet military occupies the country. Without any delay I backed him up just as firmly. Eerie silence followed, and then people stood up one by one and went home. The communist party secretary was sitting next to me. We knew him as a decent person, but in such situations he had to report these events to his superiors. A few days later an uneasy filing prevailed over me. I realized I could be in serious trouble. So, early on the morning of the 22nd of November 1956, I made the decision to leave the country. I again went to the Zalka Square and to my greatest amazement I found the same medium-sized truck with the exact same driver who had taken me into the city on the morning of the 24th of October, but this time he was transporting people strait to the Déli Pályaudvar (the main railroad station on the Buda side of the city). The station was jam-packed with people. But there were no uniformed people of any kind. On the rails, only one train that had a steam locomotive in front of it sat waiting. I asked the machinist: Where does this train go? He replied: Bécsbe! Which means To Vienna!

After so many decades I wonder: Was there an organized effort not only to provoke a revolution, but also to get rid of as many Hungarians as possible? Remember, after Stalin’s death in 1953, by 1956 things were going in the right direction, which was torpedoed by the Stalinist wing of the communist party, the very same people provoked the revolution.

Oak Forest, February 2006. Revised in 2019.

Bibliography

Békés, Csaba – Byrne, Malcolm – Rainer, János M. The 1956 Hungarian Revolution: A History in Document.

Central European University Press. Budapest – New York, 2002.

Bohlen, Charles E. :Witness to History: 1929-1969. W. W. Norton & Company, INC. New York, 1973.

Csiba Lajos : Napló, Szivárvány. 1989. szeptember.

Csonka Emil : A forradalom oknyomozó története: 1945-1956. Veritas, München, 1981

Görbedi Miklós : Szögesdrótok mögött a Sajó völgyében. Magyar Ciszterci Diákok Szövetségének Egri Osztálya.

Pongrátz Gergely : Corvin köz 1956. A szerző kiadása. 1982 – 1992.

Skousen, W. Cleon: The Naked Capitalist. Salt Lake City, 1970.

A magyar forradalom és szabadságharc a hazai rádióadások tükrében. Free Europe Press. New York

1 Szögesdrótok mögött a Sajó völgyében. Page 14.

2 Szögesdrótok mögött a Sajó völgyében. Page 73.

3 A History in Documents. Page 15.

4 A History in Documents. Page 17.

5 A History in Documents. Page 19.

6 A History in Documents. Page 19.

7 A History in Documents. Page 16.

8 A History in Documents, Page 62.

9 Witness to History. Page 367.

10 A forradalom oknyomozó története. Page 367.

11 History in Documents. Page XXXV.

12 A forradalom oknyomozó története. Page 383.

13 History in Documents. Page XXXVI.

14 Corvin köz 1956. Page 74.

15 Corvin köz 1956. Page 114.

16 Szivárvány. Page 66. (Monthly Journal)

17 Szivárvány. Page 70.

18 Corvin köz. Page 263.

19 History in Documents. Page XXXIX.

20 History in Documents. Page 209.

21 Witness to History. Pages 412-423.

22 History in Document. Page 413.

23 A forradalom oknyomozó története. Page 417.

24 History in Documents. Page XLI.

25 History in Documents. Page 268.

26 (46) Congressional Records, Volume 106, Part 14, Eighty-sixth Congress, Second Session, 31 August, 1960. 18785.