Written by Klára Friedrich

Translated into English by Margaret Botos

Contents

|

|

5/1. Hungarian builders of Kiev p. 21 5/2. Data from archaeology and history p. 22 5/3. How did Prince Álmos disappear from the history of Kiev? p. 24 5/4. Hungarian -Viking marriages p. 33 5/5. Recollections of the Vikings in Hungary p. 38 5/6. Summary p. 39 5/7. Acknowledgements p. 40 5/8. Bibliography p. 41 |

1. The Dragonboat People

Historians place the Viking age between 800 and 1100. The Vikings were descendants of the Normans or Nordmanns, that is people of the North. They were believed to be a Scandinavian tribe of the Germanic family of people.

Norman castle on the edge of the ocean (Ribáry – Molnár)

According to Antal Molnár: In the 9th and 10th centuries, the Normans established kingdoms in Sweden, Denmark and Norway. Those who wished to be free from the royal power, or those who did not possess a family inheritance and did not wish to become priests, turned to piracy and wandering in foreign lands.

“Their ships were their homes, their castles, their lands, their everything… The Norman youths, under the leadership of their princes, the Vikings, obtained their warrior training during their pirating campaigns… Their characteristics and valiant traits, in many ways were like those of their contemporaries, the kindred Hungarians. Their steeds, their faithful companions in their warring campaigns, followed their masters into the grave, and the Norman pirate kings often had their ships buried with them.” (Ribáry – Molnár, 1881/310)

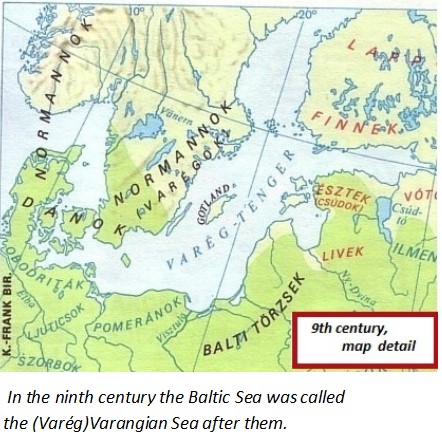

The origin of the name “Viking” is disputed. I agree with István Kovárczy that the word developed from the words “water king”. They were also called “Varégs” or “Varangians”. According to some sources, the Swedish Vikings were the Varégs, because in their language the name of their state is “Sverige”. According to others, they received their name from the Slavs.

In 911, the Viking commander, Rollo, established the principality of Normandy. His descendant, the Norman prince, William the Conqueror, captured the English throne and, from 927, the Vikings occupied the throne of England for 227 years.

The battleship of the Norman, William the Conqueror, on his way to conquer England in 1066. (P.Dixon)

Illustrated information about the life of the Vikings can be seen in the Bayeux (France) tapestry, which was created in around 1070, a beautiful colored work, 70 meters long and half a meter wide. Its main theme is how the Normans conquered England in 1066.

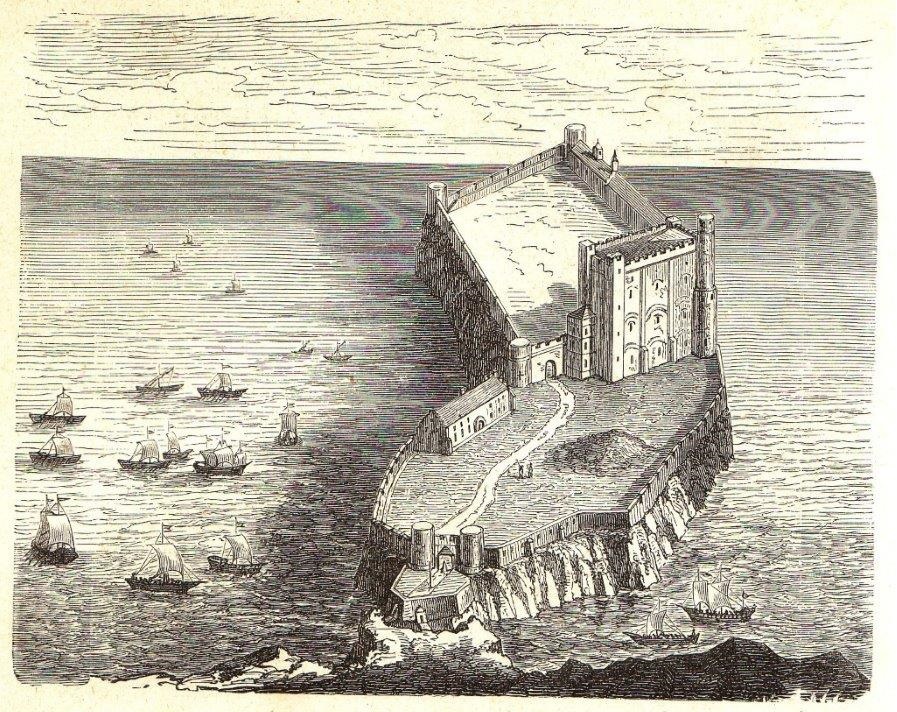

Greenland was discovered by a Viking called Erik the Red (Erik Raude) in 982. According to the Greenland legends, the discovery of America is also attributed to the Vikings, approximately 500 years before the voyage of Columbus in 1492. “One sign of this discovery is a rock face full of runic script.” (Ribáry – Molnár, 1881/310)

In 986, a Viking sailor wanted to travel from Iceland to Greenland, but he lost his way and finally saw an unfamiliar coastline. Although he did not disembark, he took the news of his discovery home to his compatriots, among whom Leif Eriksson, (son of Erik the Red, born in Iceland) a Viking sailor and discoverer, started out, probably in 992 to explore this unknown land.

They disembarked on a grassy shore and called the land Vinland (Wineland) because Leif’s stepfather, Tyrkir, who was traveling with them, found grapes on one of his trails of discovery. Many historians believe he was Hungarian because of his name.

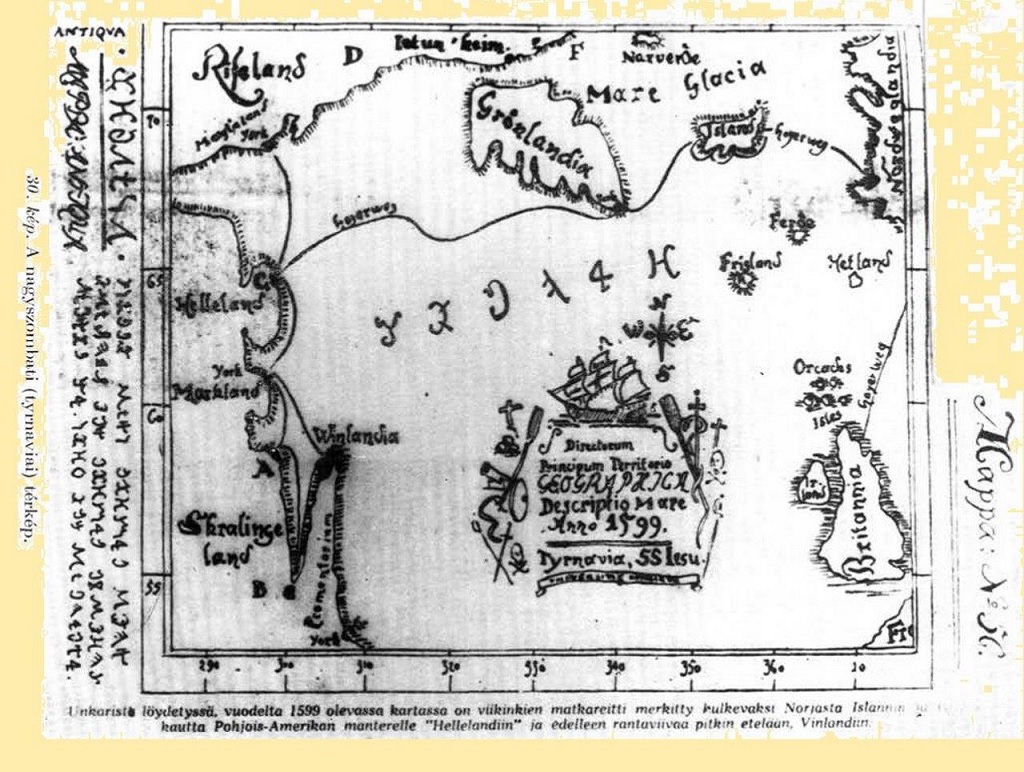

We know of five famous maps of Vinland from the 14th to the 17th centuries. On two of them there is runic script. Vinland is presently part of the Canadian province of Newfoundland.

Map of Vinland in Nagyszombat (Szepessy Géza)

There were also Magyars living in the Scandinavian territories among the Vikings. This is supported by the data from Mátyás Jenő Fehér: According to the curator of the Viking Museum in Oslo, in 1950, in an excavation of a Viking settlement, called Kaupang, archaeologists found the skeleton of an ancient Hungarian knight, together with his horse, buried in a ship. Such finds were unearthed in other Viking settlements too. (1972/64)

In 1893, archeologists reconstructed an exact replica of a ship discovered in a Viking burial mound in Gokstad, in order to find out how long it took for the discoverers of America to travel with such a ship from Norway to Vinland, 910 years ago. The sailing ship reached its goal in less than a month. (Dixon, 1985/125)

The Vikings undertook great journeys not only toward the West but in all directions of the compass. For example, they reached Paris on the Seine with 120 ships, and they were given 3500 kg. of silver to sail away again. The lead ships were decorated with the head of a dragon, so these fast vessels, equipped with sails and rowers, were called drakkars (Viking longships) after the dragons.x

On dry land, they made wheels for these ships (amphibious vehicles, a technological development!). They traded and transported goods, for example furs, skins and marine ropes made of skins…

Novgorod was a large trading center that was called Holmgard. Raymond Page, a prominent English researcher of the Vikings and runologist writes: “South of Novgorod the trade route followed the Dnieper, past Kiew to the Black Sea and the heart of Eastern Empire Byzantium as the goal. Not all Vikings came to this great capital to buy and sell. A promising occupation for a young tough was to became (sic) a member of the Varangian Guard of the Emperor.”

Antal Molnár writes: “The liberation of the capital of the East (Byzantium) from the most bloodthirsty people of the Scythians, as a Byzantine scholar called the attackers, was extraordinarily influential.” (1881/311). Unfortunately, Antal Molnár does not name the Byzantine scholar, yet it is an important piece of information for, at that time, he listed the Normans among the Scythians.

Their writing was a 16 letter variation of the common Germanic runic script.

I have written more extensively about the decipherment of the memorials written in the Russian runic script, under the Viking supremacy, in my book Hunok, germanok, rovások, runák (Huns, Germans, Runes) from page 115 on. (2020) For example, Halfdan, a member of the Varangian (Viking) Guard, carved his name in runic script in the marble balustrade of the Hagia Sophia Basilica.

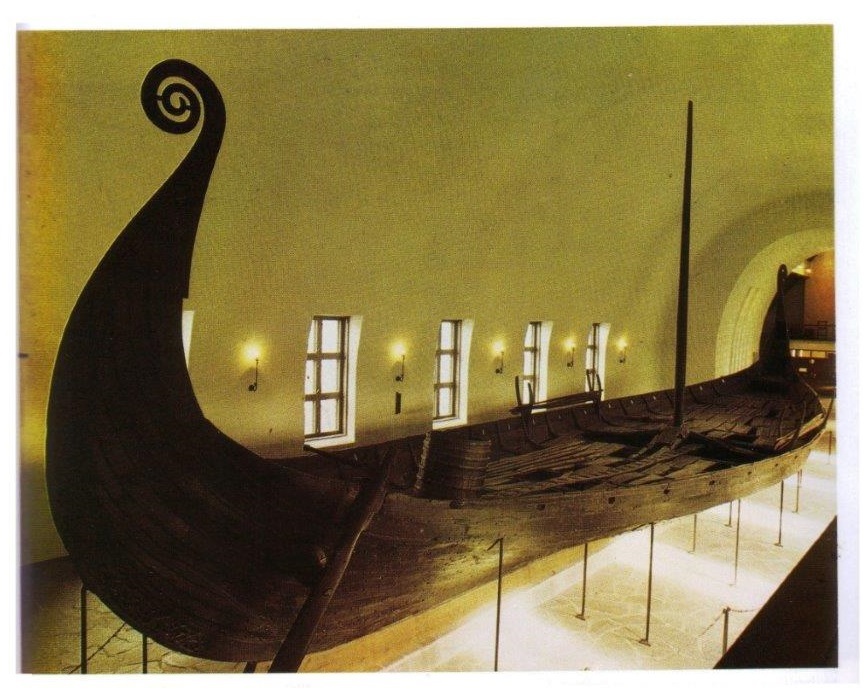

Their most characteristic custom was the ship burial. For the burial of the high classes, a decorated ship was prepared. Its size varied but it was large enough to hold the corpse and his servant, certain artifacts to accompany him to the otherworld: food for the journey and barrels of drinks, and in the bow of the ship the dead man’s horse. Sometimes, the ship was set on fire close to the shore and sent out to sea. On other occasions, the ship was buried under a mound of earth. The most highly-decorated ship grave, the Oseberg ship, can be seen in the ship museum in Oslo, Norway. It is made of oak, 22 meters long and 5 meters wide. Two women are laid at rest in the ship grave, perhaps the Scandinavian Queen Asa and her lady-in-waiting. The Viking women were equal to the men.

Oseberg ship, 9th century, Oslo ship museum in Norway (P.Dixon)

If a warrior died far away from the Viking Sea, and there was no way to prepare him a ship burial, or if he was not rich, they arranged stones around the grave in the shape of a ship.

Viking graves (Wikipedia)

They erected grave-stones, engraved with runes, in memory of the dead. The most famous of these is the Rök runic stone. In his book, Raymond Page mentions several touching inscriptions on memorial stones. A Viking named Thorsteinn died in Kijevan Rus and his family, who lived in Scandinavia, prepared a touching memorial stone for him, inscribed with a poem in runic script. Here is a part of it:

“He died in battle, east in Russia

Leader of the guard, best of landsman...”

Viking parents erected the following inscribed memorial stone for their two sons: “One died in the West, the other in the East.”

Ézsaiás Tegnér, a Swedish poet and university professor (1782-1846) in a chapter in his book entitled Vikinga balk (Viking marine law), mentions a few of the laws in poems. Despite the merciless reputation of the Vikings, one law states:

“And peace, whoever implores you, if he has now no weapons,

He can no longer be against you,

Heaven bears a sigh, have mercy on the pale one;

He cannot answer no, only the weeds can.”

The Viking ships are often pictured with a sail striped with vertical red and white stripes. It resembles the flag of Árpád, which has horizontal red and white stripes. For example, the Mogyoródi Battle – Illustrated Chronicle.

The Hungarian “adventures” are well-known, mainly between 860 and 970, and many historians mention the prayer of unknown origin “Lord, deliver us from the arrows of the Hungarians”. It was probably originally used in connection with the Normans, not the Hungarians, for, in the Ribáry-Molnár book, we can read that the Germanic people in the time of the Vikings, said the following prayer in their churches: “A furore normannorum libera nos Domine!” That is: “Lord, save us from the rage of the Normans!” (1881/331) In any case, I am not sure that the Germanic people prayed in Latin.

“The enemies of the Vikings wrote their history”. This is the opinion of the afore-mentioned Raymond Page. This is unfortunately, with few exceptions, true of Hungarian history written after 1867.

2. Rurik, the Hawk

The most significant achievement of the history of the Vikings was that they established the Russian state in the ninth century. Nestor, a monk in the cave-monastery of Kiev, wrote in his ancient chronicle: Poveszty vremennih let (Accounts of ancient times), that the Slavs, in 858, drove out the Vikings who owed them taxes of furs and skins. At the same time, the Kazars oppressed the Slavs in the territories that were inhabited by the Vikings and the Kazars. Four years later, in 862, the Slavs called back the Vikings, because they were more humane tax-collectors than the Kazars. Moreover, the Slav delegates asked the Vikings to unify the tribes that were unable to work together because of their continuous inner struggles, in other words, to help them establish a Slav state.

Slav delegation to Rurik (Ribáry-Molnár)

The Nestor Chronicle was created at the beginning of the 12th century from 11th century notes found in the cave monastery of Kiev and records the events from 850 to 1110. Therefore, it is also called the Kievan Chronicle. The original did not survive but it was reconstructed from the 14th century Lavrentyij yearbook. It was published in Hungarian by the Balassi Publishing House in 2015.

At the invitation of the Slav delegates, three brothers from the Rus nation, Rurik, Sineus and Truvor set out from Scandinavia, together with their entourage. They arrived first at the territory of the Staraya Ladoga (Ancient Ladoga), near Lake Ladoga, on the banks of the River Volkhov, which was an important trading center. Based on the legends, several mounds that can be found in Ladoga are believed to be burial mounds of the Rus princes. Rurik later moved south to Novgorod.

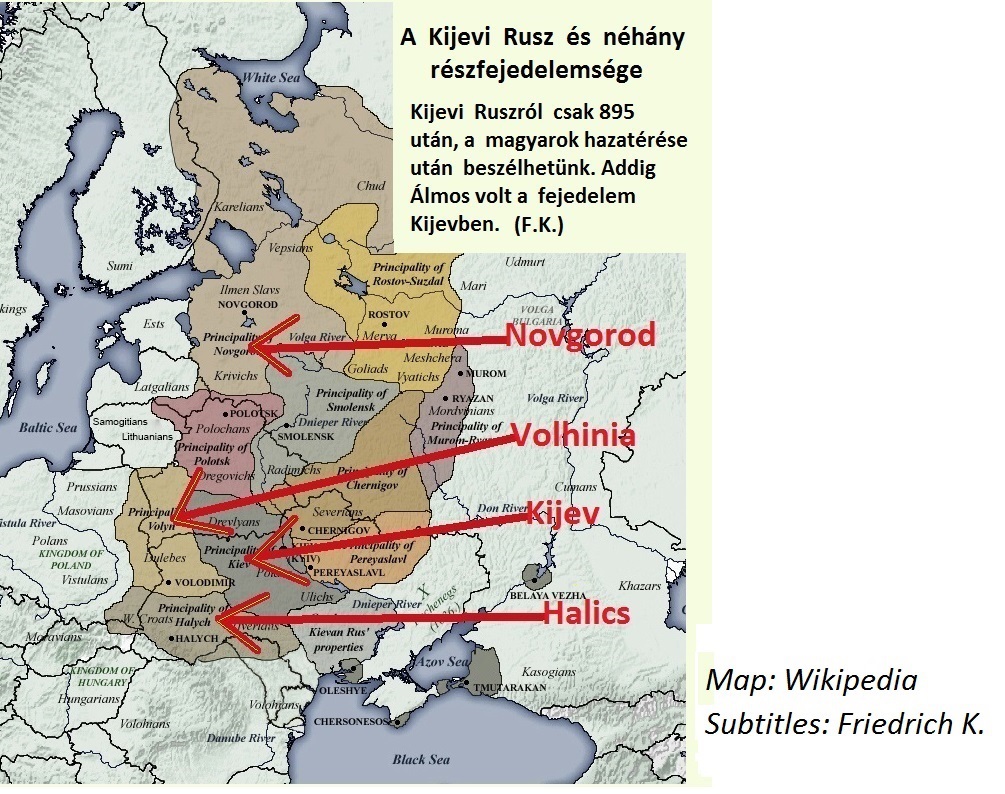

From 862 on, the three brothers united the Slav peoples, who were warring with each other, into a strong tribal alliance. They liberated them from the Kazar rule and taxation. Some historians call this tribal alliance (which was not yet a state) Kievan Rus. This is not entirely accurate because, at that time, the center of the Viking-Varangians was not Kiev but Novgorod. Of the three brothers, Rurik was the eldest and he became the leader of the tribal alliance and Prince of Novgorod.

So, Rurik, the Norman (Viking, Varég, Varangian) leader and his brothers of the Rus tribe were the founders of the Russian Empire. The name of Russia originates from the Rus nation. Likewise, the name of the Rusyns and Ruthenians. Among others, the Illustrated Chronicle and Petrus Ransanus mention Kievan Rus as Ruthenia.

It can be surmised that Rurik was born in 820, ruled from 862 on, and died in 879 or 882. His headquarters were in Novgorod. He had the fortress of Holmgard constructed beside the present-day city of Novgorod.

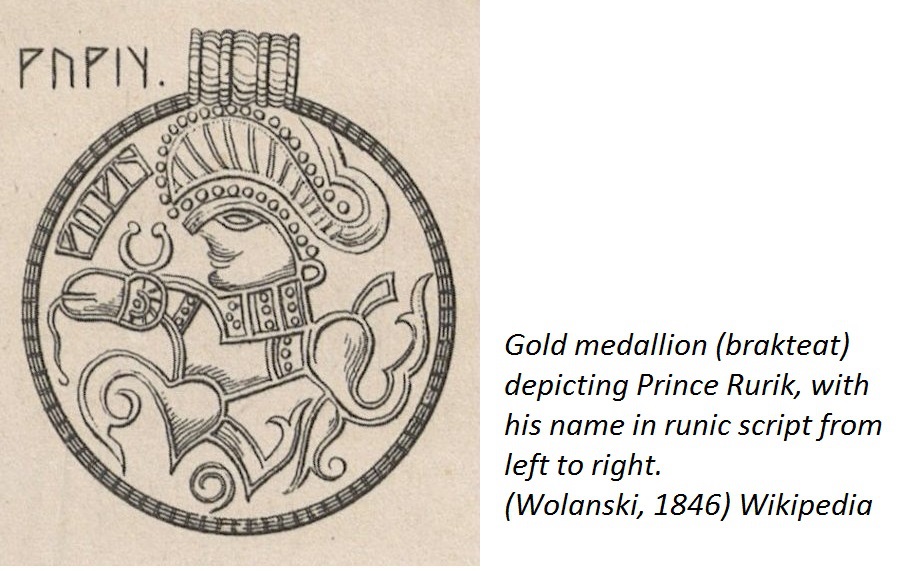

Rurik was a popular ruler. Bracteates, medallions to be worn around the neck, were produced with his name in runic script.

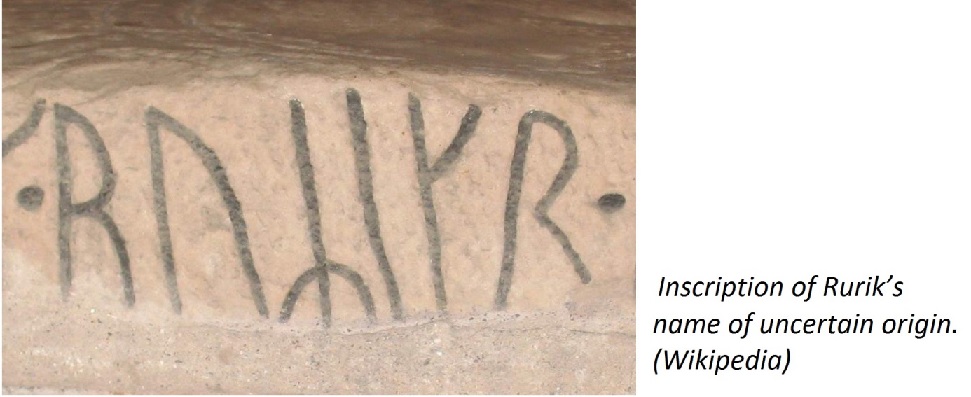

His name survived on the wall of a church in the province of Uppland in Sweden, carved into rock in runic script. However, this is not certain, because when we searched the Swedish language Wikipedia, there is no mention of this inscription. Yet the Russian language Wikipedia even shows a picture of it.

According to some researchers, Rurik did not even exist; he was a fabricated legendary personage. Such efforts must be the work of the Slavs, who wish to claim the honor of founding the state.

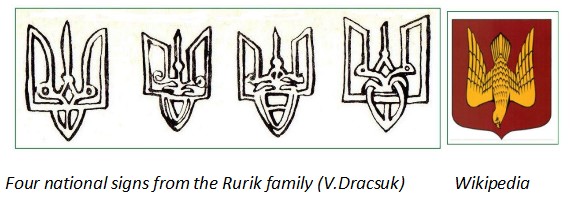

Viktor Dracsuk, a Russian paleographer, presents a group of national signs (tamga) that are recognized as the “symbols of the sons of Rurik”. They often appear on the lead seals, weapons, warriors’ belts, metal coins and jewelry originating from the Principality of Kiev. Bolszunovszkij, a Russian researcher, considers them to be letters. (Dracsuk, 1983/164, 165)

Apart from the explanation that they are letters, they have been identified as diving falcons and three-pronged harpoons. Those who consider them as falcons also believe that the name Rurik means falcon. I was very happy to discover this, because it would mean that it is related to our (Hungarian) word ráró, which, according to Mór Ballagi, is a predatory bird belonging to the class of falcons called the fisher-falcon. (1873)

The picture of the diving falcon found in Wikipedia appears on the coat-of-arms of the settlement called Staraya Ladoga (Ancient Ladoga). According to the legends, Rurik arrived here first, before he moved to Novgorod.

If we examine the tamgas, we can see that they are not quite identical. Each one is different in a small detail, so a member worthy of belonging to the Rurik nation had an individual tamga, but also a common one. The survival of these symbols is obvious since they make up the coat-of-arms of Ukraine.

Kornél Bakay writes: “… The tamgas are without a doubt the indications of a genetic relationship, and they should not be confused with certificates of ownership… the tamgas were not just used in earlier times. Tolsztov recognized the tamgas of the Rurik dynasty.. and it is obvious that there were tamgas of the Hun, Avar and Hungarian princes too.” (2005/111,112)

Rurik’s descendants originally spoke the German language but they became slavicized. For example: Rurik’s successor, Oleg, was originally called Helgi. Rurik’s son, Igor, was originally Ingvar.

On the list of the rulers of the Rurik dynasty, many names ended in “sláv”, which was rather strange sounding for people of Norman-Viking origin. I believe that this was to differentiate the children born of Slav mothers. This is sometimes difficult to trace back. For example: Igor’s wife, Rurik’s daughter-in-law, was of Slav origin. At the time of her marriage, she received the name Olga, whose German origin was Helga. We do not know Olga’s true name, because in Pszkov or Izborszk, from where she came, she was called Prekrásza, which meant “pretty”, which was probably not a name but rather an adjective. The princess, who became known as Olga, was canonized as a saint in Byzantium, because of her work in spreading Christianity, and thereafter she was called Helena. Her Slav origin is also substantiated by the fact that her son, Rurik’s grandson, was called Szvjatoszláv.

3. Vikings on the Russian throne for 720 years

The connections and marriages of the Vikings with their relatives living in Scandinavia became increasingly rarer. “Gradually, the connections with the Scandinavian ancient homeland broke down, once they adopted Christianity under Rurik’s great-grandson Valdimár (Vlagyimir), and they became one people, assimilated with the Slavs.” In this assimilation, the Slav element was represented by a great majority, but the members of the slim leading strata continued to come from the ranks of the Norman-Vikings, that is the Varangians. (Ribáry-Molnár, 1881/313)

In 965 Rurik’s grandson, Grand-Prince Szvjatoszláv I, Prince of Novgorod, divided his country among his three sons. To his eldest son, Jaropolk, whose mother was the daughter of the Hungarian Prince Taksony, he gave Kiev. He gave his son Oleg the land of the Drevljans (eastern Slavs). His son, Vlagyimir, from another mother (who was originally his mother’s housekeeper), received Novgorod.

Insert: Kievan Rus and some of its associated principalities. We can speak of Kievan Rus only after 895, after the Homecoming of the Hungarians. Until then, Álmos was the Prince of Kiev. (F.K.)

In 978, after the death of their father, Vlagyimir established an autocracy, attacked and killed his half-brother Jaropolk, Taksony’s grandson, who had legally been given Kiev, because that city had belonged to the Hungarians 100-130 years before that, in the time of Ügyek and Álmos. Vlagyimir forced Jaropolk’s sweetheart, Rognyeda, to become his wife. He moved from Novgorod to Kiev and this city became the capital city, and the name of the state became Kievan Rus.

In 980, Vlagyimir, who was still a pagan, erected five pagan idols on the castle hill in Kiev (Perun with the golden moustache, Horsz, Dazsbog, Szimargla and Mokos). Then, in 988, after he had adopted the Byzantine Christianity, he had the idols destroyed. He had the statue of Perun with the golden moustache tied to the tail of a horse, pulled down from the pedestal, beaten with a stick and thrown into the River Dnyeper. He threatened those who mourned for Perun. He organized his people on the banks of the Dnyeper, had them baptized as Christians and converted them. (Nestor, 72, 94) The Viking-Slav tribal alliance then became a Christian state. Therefore, after his death, Byzantium canonized Vlagyimir a saint in 1015, despite the fact that he had formerly had human sacrifices performed and that he had ordered his half-brother killed.

Kornél Bakay writes: “One thousand years before this, “Rus” was the territory of the united principalities of Kiev and Novgorod. The first princes ran down the Slav tribes one by one: the Drevljáns, the Szeverjáns, the Radimicses and the Vjaticses and so, by the eleventh century, the lands of Kievan Russia extended from the Carpathians to the River Oka, that is to the Northern Caucasus. Because of the conflict between their interests of power, the Russian and Byzantine armies and fleets often came face to face. Therefore, the Russians began to expand toward the East. In 964, they overthrew the formerly immensely powerful Kazar kaganate and waged war on the nomad Pechenegs, who were at that time allies of Byzantium. The Pechenegs killed Szvjatoszláv, the Prince of Kiev himself.” (1981/10)

Rurik’s nation remained in power for 720 years. From them originated the Russian rulers, the Czars. The last member of Rurik’s dynasty, Czar Fedor I, died in 1598. After him came Boris Godunov and then, in 1613, the Romanovs followed. According to other sources the Russian Czar Vaszilij was the last of the Ruriks, in 1610.

4. Ancient comrades-in-arms: Huns - Germans

Since the Normans (Vikings, Varangians) were of Germanic origin, we need to step back about four hundred years to the time of the Huns. I offered many examples of their good connections in my book entitled: Hunok, germánok, rovások, runák (Huns, Germans and runes). Of these, I quote from an “objective” historiographer, the Goth, Jordanes: In 451, at Catalaunum (Chalons) “there was the very famous king of the Gepidas, Ardaricus and his innumerable military columns, who, because of their steadfast loyalty to Attila and in consideration of this, were also present. Indeed, Attila wisely and carefully weighing the situation, respected him and Valamer, the king of the Ostrogoths, more than all the other kings.” (Section 199)

There were also marriages between the Huns and the Germans. Balambér, King of the Huns, great-grandfather of Attila, married the granddaughter of Venetharius, the King of the Ostrogoths. Attila was also married to three German women, the last of whom unfortunately caused his death.

I surmise that the name of the Hun king Roga can be traced back to the name of the Viking prince Rurik, and moreover, the territory called Rugiland at the time of the Huns, which is now in Austrian hands, and the settlement called Rogaland, in the Norwegian territory, can be connected to his person.

Roga, Attila’s uncle, died in 434. His name and variations of it in domestic and foreign sources indicate that he was an internationally recognized ruler. In my book Roga hun király (Roga the Hun king), in a special chapter, I write about these name variations. For example, in the books I used as sources, I found the following: Rua, Rhuas, Ruga, Rugila, Roga, Rohas, Rhoilas, Roas, Ruas, Ruha, Rőv, Rhoá, Reuva, Rova, Reva, Roka, Rof, Roff, Rov, Roua, Rú, Rowa, Reuwa, Rewa, Roilas, Rugo, Rouas, Röt, Richa, Rok, Roa, Roila, Roe, Hroar, Reuwila, Ruf, Rugha, Rugas… And even more settlement names and geographical names can be connected to his person in the Carpathian Basin and its surroundings. (2009/62)

István Bona writes in his book, Hunok és nagykirályaik (Huns and their kings) (1993): Ruga’s name “with a silent G preserved the northern German too: Roe, Hroar…”

Two Scandinavian forms of the Rurik name are very similar to this: Hroekr, Hroerekr. A few more variations of the name Rurik: Rorik, Riurik, Ryurik, Rourig. The Greek form of the Rus nation: Rhos. The river name ’Rosz’ is also in this territory.

The connections to the name Roga are shown in the names of Norman-Viking personages like those that appear in the Chronicle of Nestor: Prince Rogvolod and his daughter Rognyeda, and also Ruald and Ruar. In the vicinity of Halics, there is a territory named Rogozhin too. The use of the names Roga and Rurik indicate the sound change from U to O: Ruga-Roga, Rurik-Rorik.

I believe that one of the titles or honors of Saint Imre was connected to the name Roga. Bálint Hóman, a historian and university professor, in his commemoration written in 1930, mentions the fact that the writer of the Hildesheim Yearbook calls Imre dux Ruizorum. According to Hóman, Ruizorum was the territory between the Lajta and Fischa rivers that was returned to the Hungarians in 1030. It was the ancient Rugiland and Imre became the prince and leader of this territory. The Rugi were a Germanic tribe in the 5th and 6th centuries, which in my estimation adopted the name Roga (Ruga) out of respect for Roga and the name of the territory of Rugiland originates from this.

According to the archaeologist Csaba Bálint, in this data the word dux

means the leader of the royal bodyguard and Ruizorum refers to the Rus people (Varégs, Varangians). (2012-2013/10)

It is not rare that the name of a ruler has been preserved over centuries because of the historical events taking place in nations scattered across many territories. This is convincingly proven in the preservation of the name of Attila, the great Hun king, in the British dynasty of Etheling, found among others in the book of Zsuzsanna Somos, entitled: Attila nagykirály, a négy világtáj ura és hunjai (Great King Attila, lord of the four corners of the world, and his Huns). In this book, she also mentions that the wife and mother of King András I were both Varangian-Rus princesses. (2020/32-37)

But let us return to the 9th and 10th centuries!

5. Hungarian Connections

5/1. The Hungarian builders of Kiev

In the Nestor Chronicle, there is mention of Kij, Scsek and Horiv, who were Poljan (Eastern Slav) landowners and builders of castles, who also built the city of Kiev (Kijev) in honor of their eldest brother, Kij. According to George Vernadsky a Russian-American historian (1887-1973) and Viktor Padányi, a Hungarian historian, the three builders were not Slav but Magyar, and their names were originally Keve, Csák and Geréb. Padányi dates the completion of the construction at 840. (1956, 1989/325)

According to the historian Mátyás Jenő Fehér, the three builders were Avar, so Kiev was founded by Avar-Magyars. (1972/5-15)

Although through no fault of my own, I am neither a historian nor an archaeologist, but just a well-read, thinking Hungarian teacher, it is my opinion that, in this territory, as in a large part of Eurasia, we can speak of earlier Scythian-Hun supremacy and civilization. The transmitters of this civilization, however, did not disappear into nothing, so it is quite natural that the art of construction in this territory was passed on by the descendants of the Scythian-Huns, the Magyars, before the appearance of the Norman-Viking-Varég influence in this territory. Therefore, it is not impossible that truly the first buildings in Kiev can be attributed to the Hungarians: Keve, Csák and Geréb.

Two important principalities, besides those of Kijev and Novgorod, were those of Halics and Volhinia. In both, the Viking-Rus princes married Hungarian princesses, as we shall see later. King Mátyás was also the ruler of Halics and Volhinia (Lodoméria).

5/2. Data from archaeology and history

Gyula László writes: “… In the archaeology of our homeland, we can find northern, Viking connections in the tenth century.” (1974/180.)

György Győrffy writes in his book: István király és műve (King Stephen and his work), that, in the bodyguard of King (Saint) István, there were Varangians serving alongside the German knights. (1977/313)

In this same book we can read that, among the auxiliary people serving as border-guards for Prince Taksony, were the Scandinavian-Varangian Kulpins. (1977/64) Their significance is demonstrated in many place-names and names of bodies of water. According to Anonymus1, the father of the valiant knight, Botond, was also called Kölpény (Kulpin). (parts 41, 53, 56)

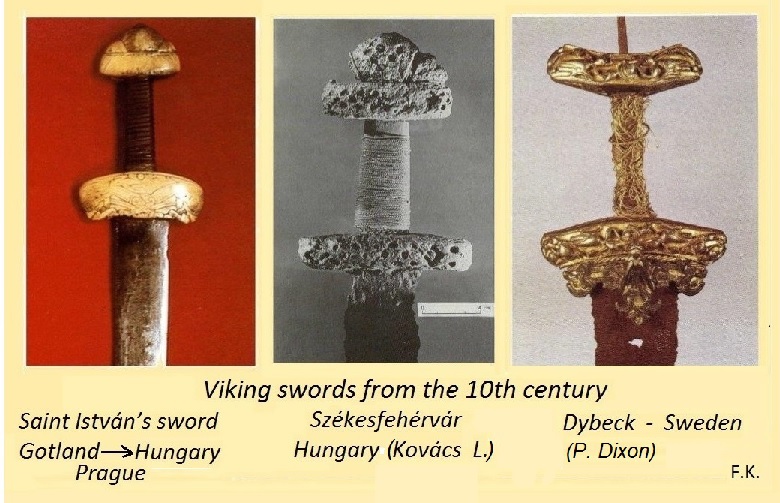

The Hungarian Katolikus Lexikon writes about the sword of Saint István (Stephen) abbreviated: It was created around the year 1000 in Gotland (a Swedish island) or in Jutland (a Danish island). The pommel of its hilt and the guard are made of bone. On the guard are carved animal shapes and ribbon patterns. It is kept in the treasure- house of the Saint Vid cathedral in Prague and, in the inventory prepared in 1335, it is called the sword of Saint István. Princess Anna, the daughter of King Béla IV, at the time of the death of her father, took it from the royal treasure-house.

1 Anonymus: Twelfth century chronicler, whose name is unknown.

Saint István’s sword (Gyula László: Árpád népe)

Ildikó Hankó anthropologist, writes: (Magyar Demokrata, 2020/34) “This is the sword that was worn by the young István in 997, when he was preparing for the duel against Koppány. This could be the sword that the escort of Queen Gizella, the German knights, brought to the prince.” This certainly must have been a product made abroad, because a Hungarian swordsmith would not have made a sword to be used against Koppány. (F.K.)

Csaba Bálint archaeologist, in his study: IX-XI. századi magyar-skandináv kapcsolatok régészeti nyomai (9th-11th century Hungarian-Scandinavian connections on the basis of archaeology) abbreviated (can be found in the bibliography):

On the basis of archaeological finds, Nándor Fettich was the first to demonstrate that there were trading connections between the Hungarians and the Eastern European Vikings. Similarly based on the writings of Nándor Fettich, István Fodor concludes that, based on the spread of the satchel decorations in Eastern Europe attributed to the Hungarians, the noble Varangian and Slav founders of the Kiev state adopted the custom of decorating satchels from the Hungarians and transmitted it to the North. According to him, Hungarian smiths produced the fittings. The peaks of the conical caps, the helmets, stirrups and two-edged swords were very similar. The Budapest lance was probably made in the first half of the 11th century in Gotland.

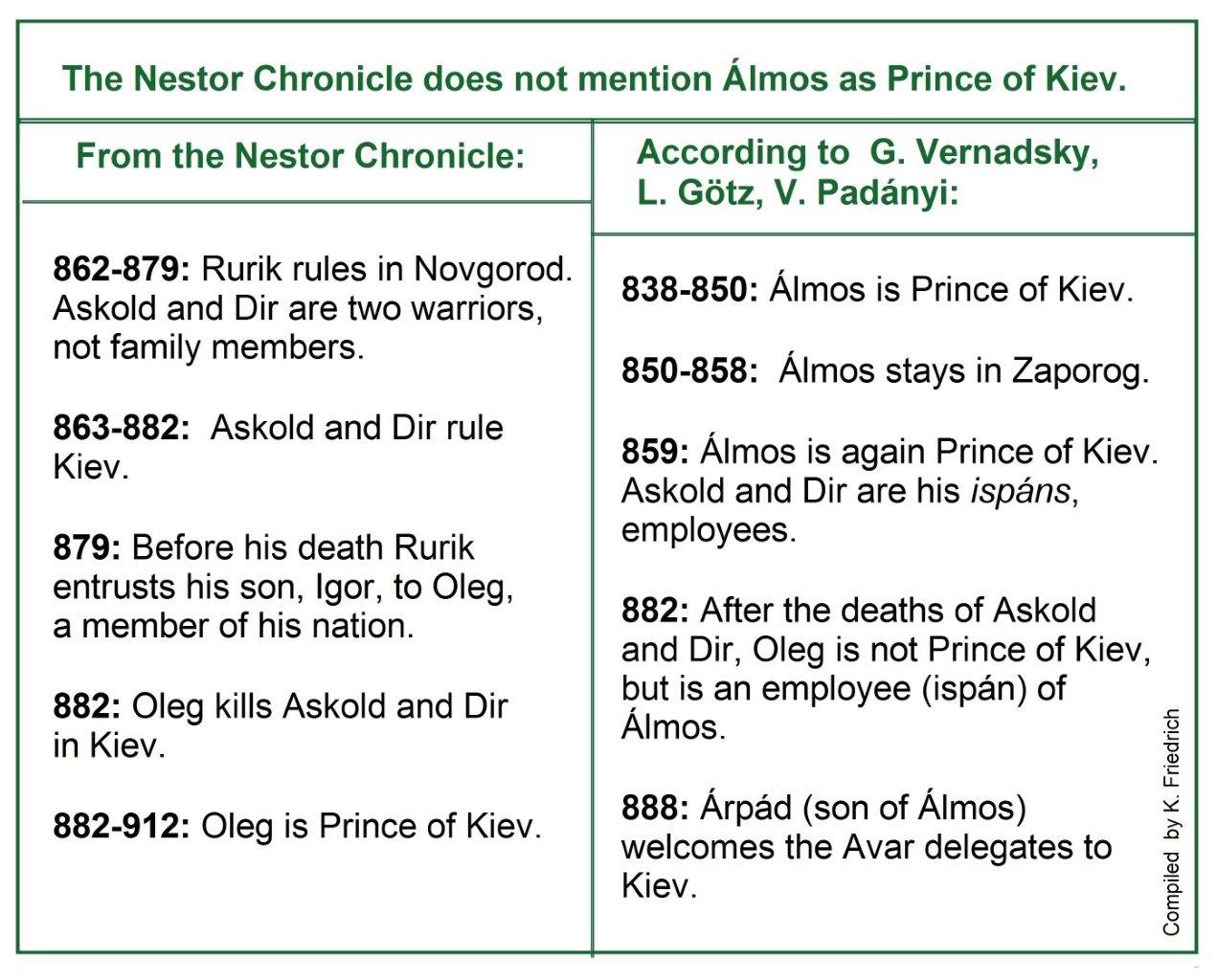

5/3. How did Prince Álmos disappear from the history of Kiev?

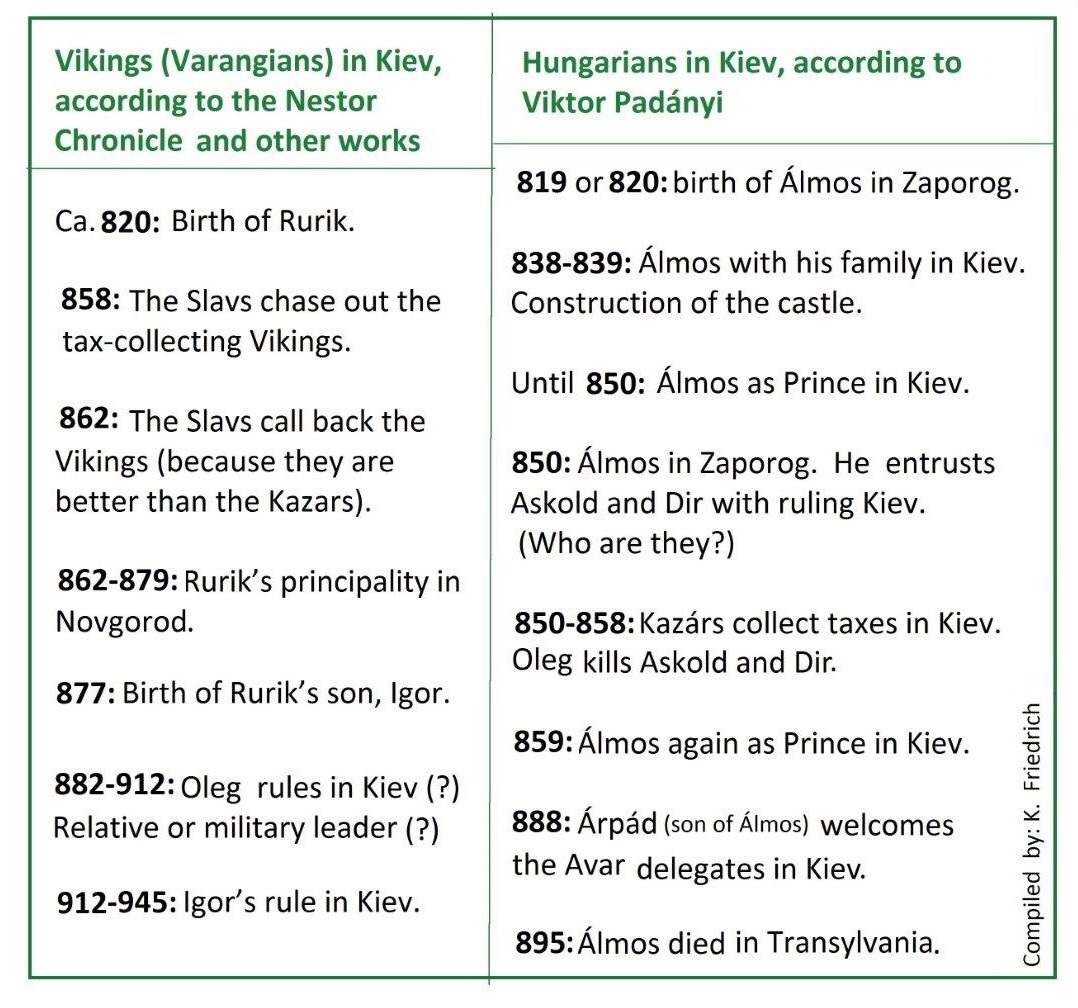

I find that, in the studies that deal with the Viking- Hungarian connections, there is a lack of information about the time that Álmos was the Prince of Kiev. It is hardly mentioned. The historian Viktor Padányi and a few of his scholarly colleagues have made up for this lack in their works, so I shall quote from a few of these.

On the basis of Viktor Padányi: Prince Álmos (819 or 820-895) spent his childhood in Dentu-Magyaria, in Zaporog, one of the cities established by the Megyer nation on the banks of the River Dnyeper. (Presently, this territory is part of Ukraine.) His parents, Ügyek and Emese, moved 400 km north on the banks of the Dnyeper and they began to construct a stone fortress in Kiev, in 820. This construction was completed by Álmos, who became Prince of Kiev and organized the most advanced production of swords in the world and also organized the return of the Hungarians to their ancient homeland in the Carpathian Basin. The Kiev sword in the second half of the 9th century was a much sought-after item of world trade.

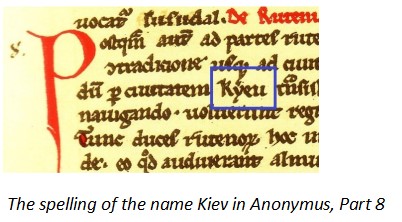

According to Viktor Padányi, the origin of the name Kiev was Keve, that is the word kő (which means stone). I believe that this opinion is supported by the way the name Kiev is written in the Gesta of Anonymus: Kyeu. The Latin alphabet does not contain the letter Ő, so that was the only way they could write the word KŐ. (In the ancient Hungarian writing there was and still is a letter for every sound, including the letter Ő.)

After living in Kiev for 10 years, in 850, Álmos had to return to Zaporog, perhaps because Ügyek died. In his absence, he entrusted Askold and Dir with the leadership of Kiev. The personages of Askold and Dir were mysterious. According to the Chronicle of Nestor, they were warriors of Rurik, bojárs (noblemen), but they were not of Rurik’s nation, and they ruled in Kiev. Padányi, quoting George Vernadsky, a Russian-American historian, writes that they were not the rulers of Kiev, but rather bailiffs or stewards (ispáns) of Álmos. According to the Czuczor-Fogarasi Dictionary, the word ispán meant a ruling official, an overseer or the manager of a county. According to Kornél Bakay: “The ispán was the supervisor of the public law and order, the executor of the laws… The ispán could enforce law and order with armed force and impose his judgment too.” (1981/115)

In the meantime, Rurik died in Novgorod, but, before his death, he entrusted his son, Igor, and the Principality of Novgorod to a person from his nation called Oleg. In 882, in a plot, Oleg had Askold and Dir killed. “… and they took their corpses to the mountain and buried them: Askold in the mountain that is now called Ugorszkoje, where the manor-house of Olma (Olmin dvor) is located and above his grave the church of Olma Saint Miklós was built. The grave of Dir, on the other hand, is behind the church of Saint Irene” .” (Nestor Chronicle, 12. 2015/33)

According to some historians the expression Olmin dvor refers to the manor-house or palace of Prince Álmos in the Ugorszkoje (Magyar) mountain. Other historians dispute this. The truth is probably what we learn from the archaeologist Nándor Fettich:

“The Soviet view of history absolutely gave precedence to the ability of the Slavs to establish a state. They did not even hesitate to use fabrications, which are heavily represented in the history writings of the Russians in the last century. For example, on the tenth century map of Kiev in the Russian chronicles, “the palace of Álmos” in the territory of the afore-mentioned “Ugorszkoje” (Magyar hely!* (place) appears as “OLGIN dvor” or “the palace of Oleg”. In contrast to this, in the ancient Russian chronicles, we see “OLMIN dvor”, which, on the basis of ÓLMA = ÁLMOS can be understood as “the palace of ÁLMOS”. In the Soviet archaeological literature, there was an official trend to completely ignore the role of the Magyars in the issue of the founding of the state of Kiev.” (1972/66)

*Fettich writes “Magyar hely (place)” and not “Magyar hegy (mountain)”.

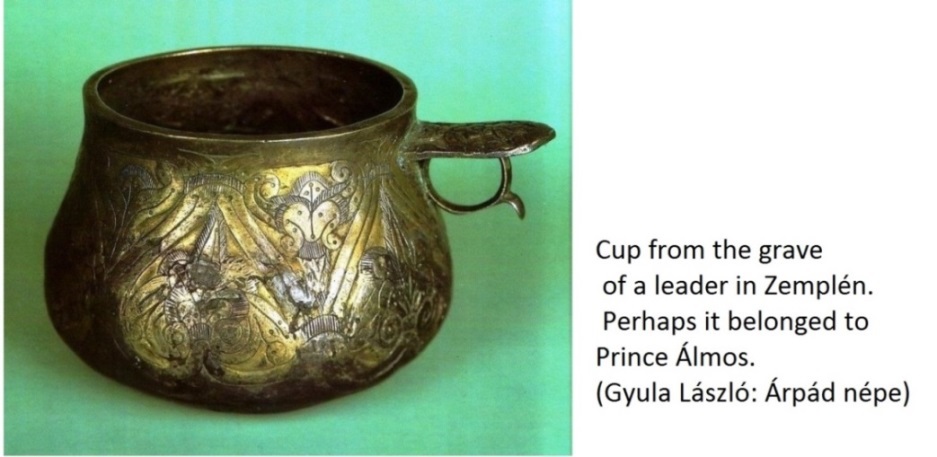

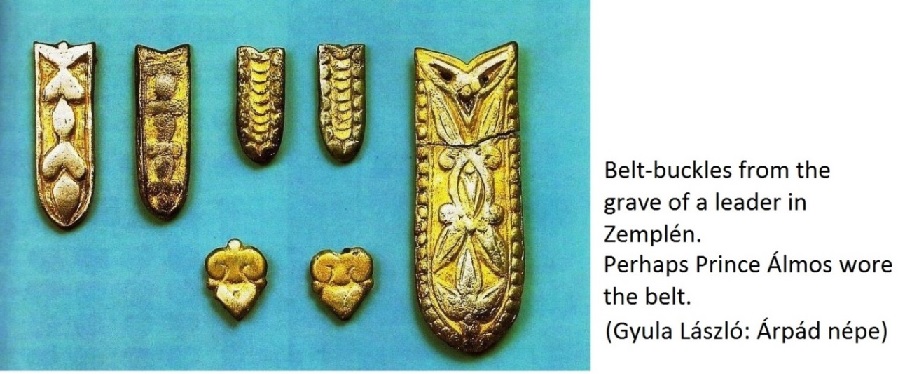

This quotation demonstrates how the Communists stripped one of the most outstanding Hungarian archaeologists, Nándor Fettich, of his status as a corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences, a position he held before 1945, and after that, he had to provide for his family as a laborer and a producer of tin toys. In any case, his opinion is that Prince Álmos was buried in Szélmalomdomb in the vicinity of the hillfort at Zemplén. (Kanyó F. 2017. 09. 13)

https://index.hu/tudomany/tortenelem/2017/09/13/szlovak_regeszek_talaltak_meg_almos_sirjat_fettich_nandor/

After the murder of Askold and Dir, Oleg ruled in Kiev, according to the Nestor Chronicle. However, according to Padányi, Oleg “was the leader of a gang of pirates, Norwegian or Danish condottieri (mercenaries)” who was not the ruler of Kiev, but the ispán or bailiff of Álmos. (1989/353) I would like to add that the ispán was not a (land)owner or a ruler, but an employee, therefore according to this, Oleg was an employee of Álmos.

Furthermore, Padányi referring to Anonymus writes that, in 888, Árpád welcomed Avar delegates to Kiev. (1989/353) Unfortunately, I was unable to find this reference in the work of Anonymus. Yet it would be important as a proof that, from 882, not Oleg but Álmos or Árpád was the prince of Kiev.

Likewise, László Götz, referring to Vernadsky, writes that, from 840 or 850 Álmos ruled in Kiev. Indeed, according to the Nestor Chronicle, the corpses of Askold and Dir, who were murdered by Oleg, were taken to the palace of Olma, to the hill that is called Ugorszkoje. Olma is none other than Álmos. (Götz, 1994, I. /231)

László Götz also refers to Nándor Fettich, who established that, among the obviously Hungarian satchel decorations, many came from the territory of the state of Kiev. This indicates that Hungarians lived here too. The relationship between the Normans and the Hungarians was peaceful and many Varangians came with them into the Carpathian Basin. “All these conditions show that the state of Kiev in the ninth century was under Hungarian supremacy, and even more to the east the Hungarians ruled the region of Szaltovo.”, wrote László Götz quoting Fettich. The Soviet archaeologists Zakharov and Arendt also came to the same conclusion when they stated that the Hungarians were the lords of the lower and middle course of the Dnyeper. (Götz, 1994,I. /231,232)

László Götz explains that “the first political schemes that can truly be called Slav, from the point of view of people and language, appeared on the stage of history only after the fall of the Avar Empire (beginning of the 9th century) and the decline of the Danube Bolgar power (middle of the 10th century), mainly not even then independently, … but for the most part in the west under the direction of the Avar originated leading class, in the south, dependent on Byzantium, in the east under the leadership of the ruling classes of the conquering Norman-Varangians – in Novgorod, and later, -- after the departure of the Magyars – in Kiev under the Ruriks, in Poland under the rule of the Piaszt family (also probably of Norman origin) and under the rule of their Norman military escort.” (Götz, 1994/II. 599)

Dezső Dümmerth, also referring to Vernadsky, writes: “… G. Vernadsky assumes that, after 860, Álmos was also Prince of Kiev.” (1987/20)

Mátyás Jenő Fehér writes: “According to the logical interpretation of Fettich, the entirety of the Hungarians did not leave the iron-working centers, but, with new “methods”, continued their craft and, in Kiev itself, the Hungarians can be shown to have survived even into the beginning of the 13th century.”

Márta Font historian: “It seems to me that Oleg must have led the Varangian Rus down from Novgorod, settled in Kiev and begun engaging in military activities in the area between Kiev and the Black sea, after the Hungarian tribal confederation had completely vacated the Etelköz - that is to say the Hungarians’ departure in 896…” (2021/103)

Similarly, the dominant and ruling position of the Hungarians is proven by the following sentence, which I read in the work of George Vernadsky, a Russian-American historian (1944/26): “…about 858 a band of their warriors (i.e. Rurik’s warriors) succeeded in reaching Kiew and in establishing themselves there under an agreement with the Hungarians.

Kornél Bakay rightfully rejects the opinion of Gyula Kristó, who writes that the Hungarian principality was a puppet state, subjected to the Kazars, and Levedi and Álmos were puppet princes of the Kazars. “…his statements are completely malicious assumptions, without any historical base.” (Bakay, 1998/68)

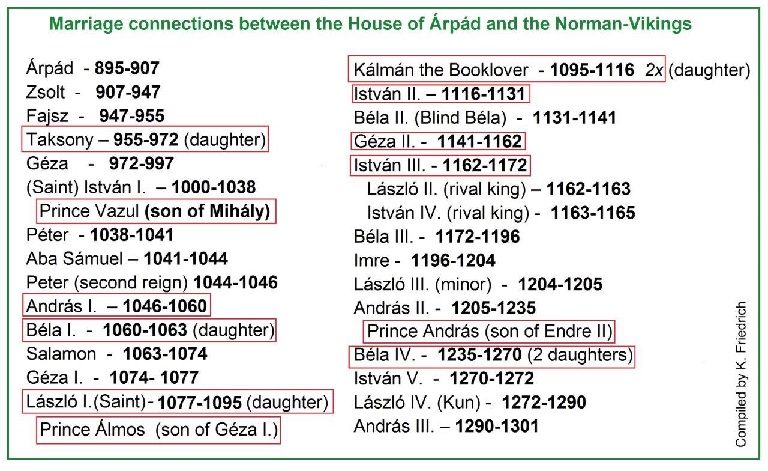

The question arose in my mind that, if George Vernadsky, Viktor Padányi, Mátyás Jenő Fehér, Dezső Dümmerth, Nándor Fettich and László Götz write that Álmos and his family and courtiers played such an important role in Kiev, why is Álmos not mentioned in the Nestor Chronicle, which was written 250 years later in this same city? In my opinion, on the one hand they were trying to diminish the importance of the memories of the pagan era, and on the other hand they were purposely making the role of the civilized Hungarian insignificant so that they could increase the importance of the rise of the Slavs, but the main reason could actually be the second marriage of King Kálmán.

The second marriage of Kálmán the Booklover (1074-1116) was to a Norman-Viking woman, who was not from the West but from Kievan Rus. Eufémia (+1139) was the daughter of Vlagyimir II. (Monomach, 1053-1125) Grand Prince of Kiev. Antal Molnár writes that “She brought sorrow on the head of King Kálmán; this marriage was the source of many troubles. This Russian princess was with child when she came into the arms of her royal husband. Kálmán sent her back and Borics, to whom the rejected woman had given life, grew up as an adventurous pretender to the throne.” (Ribáry-Molnár, 1881/653)

In any case, Kálman can be considered to be courteous in this matter. If this had happened to Eufémia in the “civilized” West, for example in the court of Henry VIII, she would certainly have returned to her parents’ house without her head.

We do not know exactly what could have happened. It is quite possible that Eufémia did not wish to convert from the Byzantine Christianity to the Roman Christianity. (Kálmán was not only king, but also a Catholic prelate, the Bishop of Nagyvárad and Eger.) Borics (Boris) was born in Kiev and the Hungarian Chronicles mention him as an illegitimate heir, however Kálmán never acknowledged him as his son. On the other hand, the Byzantine emperor, Joannész II, supported Borics in his claim to the throne and gave him a Byzantine princess as his wife. Borics asked for and received help from the Poles, Germans and French in his bid to acquire the throne but he was unsuccessful. He named one of his sons Kalamanosz, and he held fast to his claim that Kálmán the Booklover was his father. Eufémia died in a convent in 1139.

I surmise that this unfortunate marriage was the reason that the Hungarian presence and Prince Álmos were left out of the Nestor and later Russian chronicles. Moreover, Eufémia’s father, Kálmán’s father-in-law, Vlagyimir II. (Monomah) was ruling in Kiev at the time of the writing of the Chronicle, from 1113 to 1125. The Nestor Chronicle that was written in 1113, was re-written twice: in 1116 and in 1118, both times under the reign of Vlagyimir II. (Monomah). I believe that the offended father-in-law, who, in addition was hoping that his grandson, Borics, would become king of Hungary, retroactively took out of the chronicle any reference to the activities of the Magyars and the rule of Prince Álmos.

In the interests of clarity, I have prepared a table:

5/4. Hungarian -Viking marriages

The marriage connections between the Hungarian kings and the Norman Rurik Royal House have been most accurately recorded by the historian and university professor Márta Font from Pécs: “Among the marriage connections of the House of Árpád, the Rurik dynasty is in first place, with 15 marriages.” Her study can be found in the bibliography.

1. The daughter of Prince Taksony (931-973), whose name unfortunately we do not know, married Szvjatoszláv, the Prince of Kievan Rus, grandson of Prince Rurik of the Vikings. She bore him two sons, Jaropolk and Oleg. (This fact can be found in an article by Márta Font from 2012, but it is not mentioned in her book in English that appeared in 2021.)

In a study about Joachim, the Bishop of Novgorod, I found the detail that Szvjatoszláv’s father-in law was the prince of the Ugors. At that time, Taksony was the Prince of the Hungarians, so this detail supports the fact that it was his daughter who was in question.

Szvjatoszláv had two marriages and a son called Vlagyimir (Volodimir). I have mentioned him before, stating that in order to claim Kiev, he killed Jaropolk, Taksony’s grandson, and he was later canonized a saint, because he converted the Slavs to the Byzantine Christianity.

2. Prince Vazul* (Vászoly, 990-1037) married Predszláva (or Premiszláva – according to Dümmerth). Predszláva’s father, that is Vazul’s father-in-law, was the aforementioned Grand Prince Volodimir, later canonized as Saint Vlagyimir.

*In this study, I shall not deal with the uncertainties surrounding Vazul, László Szár, László Kopasz, Zerind Tar and Koppány, or their contradictions, because just the mention of the sources would be longer than this entire study.

After Vazul was persecuted, assassinated and his body mutilated (so that he would not be the next king after Saint István), his sons, András, Béla and Levente fled to the Czech state and Poland and finally found refuge among their Viking relatives in Kiev.

3. András I. (Endre, 1015-1060) was converted to the Byzantine Christianity in Kiev. He married Anasztázia, the daughter of Jaroszláv the Wise (979-1054) and the Swedish princess, Ingegard. From this marriage, King Salamon was born, who was therefore the grandson of Jaroszláv the Wise.

In Tihany, a statue was erected of the royal couple. Here, Anasztázia had a monastery built from stones brought from Kievan Rus. According to some sources, these were the hermit dwellings named Oroszkő (Russian stones), built on the pattern of the cave monastery in Kiev for the monks of Byzantine Christianity. Anasztázia supported the reign of her son Salamon, with the help of the Germans. In the interest of this, she sacrificed many Hungarian treasures. For example, she gave the sword of Attila to Ottó of Nordheim, the Prince of Bavaria, which became one of the coronation accessories of the Holy Roman Emperors.

4. King Béla I. (1016-1063) gave his daughter, Ilona, in marriage to the grandson of Prince Jaroszláv the Wise, Rurik Rosztyiszlavics, the Prince of Halics.

5. Jaroszláv, Prince of Volhinia (+1106), married the daughter of Saint László, whose name is not known.

6. Prince Álmos (1075-1127), the younger brother of King Kálmán the Booklover, married Predszláva, the daughter of Szvjatopolk II (1050-1113), the Grand Prince of Kiev.

7. The first marriage of Kálmán the Booklover (1074-1116) was to the Sicilian-Norman princess, Felícia of Hauteville. She came from the House of Hauteville and not from the House of Rurik.

8. Kálmán the Booklover’s second, but unsuccessful marriage to Eufémia, the daughter of Vlagyimir II, Grand Prince of Kiev, is noted on page 29.

9. Zsófia, Kálmán the Booklover’s daughter from his first, Norman marriage, married Volodimirko I. (Vlagyimir) (+1153), Prince of Halics, who originated from the Rosztyiszláv branch.

10. István II. (1101-1131), firstborn son of Kálmán the Booklover’s first, Norman marriage, unfortunately belongs in the list of short-lived kings of the Árpád House. His first wife was a Norman princess, Krisztina of Capua, daughter of Prince Robert of Capua.

11. In 1146, Géza II. (1130-1162) married the daughter of Grand Prince Misztyiszláv I. (the Great) and a Swedish princess: Eufrozina (Fruzsina, in the ancient lexicons).

12. István III (1162-1172) was engaged to Jaroszlavna, the daughter of Jaroszláv, Prince of Halics, but this engagement was broken. Based on Ferenc Makk’s book, Gyula Kristó surmizes that this decision was in the interest of strengthening the connections with the West, because then, in 1166, he married Ágnes, the daughter of the Austrian Prince Henrik II. (1988/204)

Dezső Dümmerth writes that István III. “sent home” the Princess of Halics, who at that time was already living in Hungary. (1977/347)

Ferenc Bánhegyi writes in his study on the Internet: Árpád-házi királynék (Queens of the Árpád House) that Jaroszlavna was born in 1150 and at age 16 was already engaged to István III, but either the engagement or the marriage fell apart. (This can be found in the bibliography).

13. Prince András (1210-1234), son of András (Endre) II, married the daughter of Misztyiszláv Udaloj, Prince of Novgorod. He later wanted to divorce her, but the Pope would not give his permission.

14. Anna, the daughter of Béla IV. (1206-1270), married Rosztyiszláv III., the Grand Prince of Kiev, who, in 1239, sought refuge from the Tatars in the court of Béla IV. It was here that they fell in love. In 1270, after the death of her father, Anna fled to take refuge in the court of Ottokár II, King of the Czechs, who was the husband of her daughter, Kunigunda, taking the royal treasures with her to Prague. Despite lengthy negotiations, Ottokár never returned the royal treasures, among which were many relics, nor did he return the sword of King István. It is presently kept at the Cathedral of Szent Vid.

15. Konstancia, the daughter of Béla IV. married Prince Leó, or Lev, the son of Danyiil, the Prince of Halics, who later became king.

16. In the book of Márta Font: The Kings of the House of Árpád and the Rurikid Princes, I found the fact, that the first wife of Robert Károly (1288-1342) of the House of Anjou, was a princess of Halics, who came from the House of Rurik. (Font M., 2021/123-124) She refers to the study by Gyula Kristó, which can be found in the bibliography. Anjou Robert Károly on his mother’s side was descended from the House of Árpád. His grandmother, Mária, was the daughter of István V. and Erzsébet Kun.

It was not only among the princes and kings, but Hungarian - Viking marriages took place among the nobles too. The daughter of the bojár (aristocrat) of Halics, Szugyiszláv, married the bailiff of Sopron, called Füle, who was also a master-carpenter and a bán (nobleman). (Font M., 2017/44)

Furthermore, another indication of Magyar-Viking, Varangian marriage-connections was that the father of Botond, a Hungarian warrior (10th century), was called Kölpény, according to Anonymus. As I have already mentioned the Kölpény family originated from the Scandinavian Varangians. According to this, Botond’s mother married a Varangian warrior.

House of Árpád between 950 and 1270 House of Rurik

|

1. Husband of Prince Taksony’s daughter whose name we do not know |

Szvjatoszláv, Grand Prince of Kiev, grandson of Rurik |

|

2. Wife of Prince Vazul |

Predszláva, daughter of Volodimir I, Grand Prince of Kiev |

|

3. Wife of András I. (son of Vazul) |

Anasztázia, daughter of Jaroszláv the Wise, Grand Prince of Kiev |

|

4. Husband of Ilona, daughter of King Béla I (son of Vazul) |

Rurik Rosztyiszlavics, Prince of Halics |

|

5. Husband of Saint László’s daughter, whose name we do not know |

Jaroszláv, Prince of Volhinia |

|

6. Wife of Prince Álmos (son of Géza I.) |

Predszláva, daughter of Szvatopolk, Grand Prince of Kiev |

|

7. Kálmán the Booklover’s first wife |

Felicia of Sicily, Norman Princess (not of the House of Rurik but of the House of Hauteville |

|

8. Kálmán the Booklover’s second wife |

Eufémia, daughter of Vlagyimir Monomach, Grand Prince of Kiev |

|

9. Husband of Zsófia, daughter of Kálmán the Booklover (from his first marriage) |

Volodimirko, Prince of Halics |

|

10. István II. (from the first marriage of Kálmán the Booklover |

Krisztina of Capua, Norman Princess (not of the House of Rurik, but the House of Capua) |

|

11. Wife of King Géza II. |

Efrozina, daughter of Misztyiszláv I, the Great, Grand Prince of Kiev |

|

12. István III’s fiancée or wife |

Jaroszlavna, daughter of Jaroszláv I, Prince of Halics |

|

13. Wife of Prince András (son of Endre II.) |

Daughter of Misztyiszláv Udaloj, Prince of Novgorod |

|

14. Husband of Anna, daughter of Béla IV. |

Rosztyiszláv, Prince of Novgorod |

|

15. Husband of Konstancia, Béla IV’s daughter |

Leó, Prince of Halics |

|

16. First wife of Róbert Károly (House of Anjou) |

Mária, Princess of Halics |

Compiled by Klára Friedrich from the works of Márta Font, Dezső Dümmerth, Ferenc Bánhegyi and encyclopediae.

5/5. Recollections of the Vikings in Hungary

Anonymus – section from part 10, translated: “…many of the Russians joined the leader, Álmos, came with him to Pannonia, and some of their descendants live today in certain places in Hungary…” Anonymus also writes: “multi de ruthenis almo duci adherentes”, that is that many Ruthenians and Russians joined the leader, Álmos.

The memory of the settlement of those who came from the Rus and Kievan Rus nation is preserved in settlement names. Here are some from the collection of geographers Elek Fényes and András Vályi: Ruszka: County Zemplén, Rusz: County Zemplén, Ruszkócz: County Ung, Göncz -Ruszka: County Abaúj, Ruszinócz: County Krassó etc. Kölpény, according to the Czuczor-Fogarasi Dictionary, is a Transylvanian village in the Maros region. According to Wikipedia, the place-name Kölpény can also be found in County Bács Bodrog and County Szerém.

Traditionalists also organize gatherings that commemorate the age of the Vikings, for example a high quality get-together called “ Hungarians and Vikings at the court of Saint István” in Szigethalom. Several hundred participants, dressed in traditional costumes of the era, reproduce a settlement of the tenth and eleventh centuries with a castle, a harbor, a village and a military camp. It can be seen here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LSAFnjBIuZ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kt_TKYOro1I

5/6. Summary

The most historically significant accomplishment of the Vikings (Normans, Varangians and Russians) was that, at the request of the Slavs, they organized the Slav tribal alliance in the ninth century and, after the conversion to Christianity, the Russian state in the tenth and eleventh centuries.

The connections between the Hungarians and the Normans, and particularly the Vikings from Russland, can generally be said to be good. This is shown by the many marriages among them. It was in their common political interests to hold back the Kazars and the Byzantines.

In the ninth century, Álmos was the Prince of Kiev and Rurik, followed by Oleg, was Prince of Novgorod. Although in the Nestor Chronicle and other altered chronicles there was no mention of it, the role of Álmos as Prince of Kiev, his work in organizing the return of the Hungarians to their homeland and the operation of the blacksmith industry appear to have been undisturbed. From this point of view, there is a need for clarification of Anonymus’ glorious description of the Battle of Kiev (Part 8) and also the role of Oleg, Askold and Dir. As for Kievan Rus, we can only mention it after the departure of the Hungarians. Until then, Novgorod was the center of the Russians and the seat of the Norman-Viking princes.

It would be important to follow up with a study of the marriages that are mentioned in this article, to see in which Hungarian descendants Viking blood is flowing.

I intend to write additional supplements to this study.

As a closing thought, I quote from Kornél Bakay: “It is not an easy task to write an organized study from the oftentimes contradictory and confusing data, but research would not progress without reasonable hypotheses.” (1981/48)

5/7. Acknowledgements

Thanks to István Atilla Szőke (Kerecsenfészek, 2021) and Ferenc Bárdosi (Attila Hotel, 2022) for giving me the opportunity to deliver a lecture on this theme.

Thanks to Margaret Botos for the excellent translation.

Finally, I thank my parents for the books that were published before 1945, and Erzsike, the mother of my husband, Gábor Szakács, for the books of Ferenc Ribáry, from which I learned many Hungarian facts.

2020-2022.

My website that I share with Gábor Szakács: www.rovasirasforrai.hu

5/8. Bibliography

A magyar honfoglalás kútfői (MTA, 1900, Nap Kiadó, 1995)

Anonymus: Gesta Hungarorum (Magyar Helikon, 1977)

Bakay Kornél: A magyar államalapítás (Gondolat Kiadó, 1981)

Bakay Kornél: Őstörténetünk régészeti forrásai II., III. (Miskolci Bölcsész Egyesület, 1998, 2005)

Bálint Csaba: IX-XI. századi magyar-skandináv kapcsolatok régészeti nyomai (2012-2013) https://www.academia.edu/3465360/IX_XI_sz%C3%A1zadi_magyar_skandin%C3%A1v_kapcsolatok_r%C3%A9g%C3%A9szeti_nyomai_szemin%C3%A1riumi_dolgozat

Bánhegyi Ferenc: Öt perc történelem, Árpád-házi királynék I., II.

https://2022plusz.hu/2021/09/24/ot-perc-tortenelem-20-arpad-hazi-kiralynek-1/

https://2022plusz.hu/2021/10/03/ot-perc-tortenelem-21-arpad-hazi-kiralynek-2/

Botos László: Hazatérés (Magna Lingua, 1996)

Botos Margaret: Horse – archers and head hunters: The Fearsome Warriors of the east and the West (Magyarságtudományi Füzetek, Kisenciklopédia, 28.)

Brondsted, Johannes: Vikingek (Corvina Kiadó, 1983)

Dixon, Philip: Britek, frankok, vikingek (Helikon Kiadó, 1985)

Dracsuk, Viktor: Évezredek útján (Móra Könyvkiadó – Kárpáti Kiadó, 1983)

Dümmerth Dezső: Árpádok nyomában (Panoráma Kiadó, 1977 )

Dümmerth Dezső: Álmos az áldozat (Panoráma Kiadó, 1986 )

Dümmerth Dezső: Emese álma-virrasztó géniusz (Ifjúsági Lap és Könyvkiadó, 1987)

Fehér Mátyás Jenő: Viking kapcsolataink a 6-9. századokban (In: Magyar Történelmi Szemle (Hungarian Historical Review – Buenos

Aires, 1972)

Fettich Nándor: A kievi magyar fémművességről...(In: Magyar Történelmi Szemle (Hungarian Historical Review – Buenos Aires, 1972

Font Márta: A Kijevi Rusz hercegnője a magyar történelemben (Hromada, Magyarországi Ukrán Kult. Egyesület lapja, 2012) http://hromada.hu/2012/nom_117/tortenelem/hercegno.html

Font Márta: A halicsi magyar uralmat támogató elit

(Világtörténet, MTA folyóirat, 2017/1. szám. 33. old.)

http://real-j.mtak.hu/10874/1/vilagtortenet_2017_1.pdf

Font Márta: The Kings of the House of Árpád and the Rurikid Princes (Eötvös Loránd Research Network, 2021)

Friedrich Klára: Roga hun király (2009)

Friedrich Klára: Hunok, germánok, rovások, runák (2020)

Götz László: Keleten kél a nap I.- II. (Püski Kiadó, 1994)

Győrffy György: István király és műve (Gondolat Kiadó, 1977)

Hóman Bálint: Szent Imre (Magyar Szemle, IX. kötet, 1930/július)

Kanyó Ferenc: Régészháború Álmos állítólagos sírja miatt (Index, 2017/09/13)

Képes Krónika (Európa Könyvkiadó, 1986)

Kézai Simon: Gesta Hungarorum (Kézai Simon Magyar krónikája címen: Magyar Ház Kiadó, 1999)

Kovárczy István: A magyar-normann kapcsolatokról https://magyarmegmaradasert.hu/kiletunk/tortenelmunk/item/4839-z

Kristó Gyula: Orosz hercegnő volt-e Károly Róbert első felesége?

http://acta.bibl.u-szeged.hu/40620/1/aetas_1994_001_194-199.pdf

Kristó Gyula: Az első magyar királynék (História, 2000/1.)

Kristó Gyula – Makk Ferenc: Az Árpád-házi uralkodók (IPM Könyvtár, 1988)

László Gyula: Vértesszőlőstől Pusztaszerig (Gondolat Kiadó, 1974)

László Gyula: Árpád népe (Helikon Kiadó, 1986)

Magyar Katolikus Lexikon: http://lexikon.katolikus.hu/

Magyar Történelmi Szemle - Fettich Nándor emlékszám (Hungarian Historical Review, Buenos Aires, 1971. dec.)

Nyesztor krónika (Poveszty vremennih let - Régmúlt idők elbeszélése, 12. sz.) Magyarul: Balassi Kiadó, 2015. http://publicatio.bibl.u-szeged.hu/6261/1/MOK_30_nyomda_beliv.pdf

Padányi Viktor: Dentumagyaria (1956, Veszprém - Turul, 1989)

Page, Raymond Ian: Runes (The British Museum Press, 1987)

Radics Géza: Eredetünk és őshazánk (2002, Eredeti kiadás: 1988)

Radványi Béla: Koppány herceg és Szár László (In: Kelet Kapuja, 2021. okt. dec.)

Ransanus, Petrus: A magyarok történetének rövid foglalata (Európa Könyvkiadó, 1985)

Ribáry Ferenc: Világtörténelem – Molnár Antal: A középkor története (1881)

Rudgley, Richard: Barbárok (Gold Book Kiadó, 2002)

Somos Zsuzsanna: Attila nagykirály, a négy világtáj ura és hunjai (Püski Kiadó, 2020)

Szakács Gábor: 70 év, 70 írás (2021)

Szöllősi Antal: Norvégiai magyarok (2011)

http://ungerska.se/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=79:norvegiai-magyarok&catid=87:norvegia&Itemid=119

Tegnér Ézsaiás: A Frithiof monda (Ford: Győry Vilmos, Kiadó: Lampel-Wodianer, 1871)

Vernadsky, George: A History of Russia (New Haven, Yale University, 1944)

Lexikonok, Wikipédia

Prince Álmos

Hungarians and vikings: Connections, marriages, questions PDF ⇒