CHAPTER VI

November 6th.

I feel so queer. I feel as though there were an open wound in my head from which blood was spreading over my thoughts. How long can one bear this kind of thing ? Something must happen... We always say that, and yet one hopeless day passes after the other. All that happens is that we get news of some further disaster. The whole country is being pillaged. Escaped convicts, straggling Russian prisoners, degraded soldiers, murderers are plundering country houses, farms, whole villages, and inciting the mob to violence. Alarming news comes from all parts of the country.

Somebody came this morning from the County of Arad. Algyest; an unknown little village, which does not even appear on the map, and yet it is very dear to my heart. There, on the banks of the river Körös, are an old garden and an ancient house under the poplars... It has been broken into and pillaged. And as I heard of this, I understood the tragedy of every despoiled castle, of every ruined home in Hungary. Smoking walls, empty rooms... The venerable manor-house with its loggia was not mine, yet this misfortune touched me to the quick : they have injured the past summers of my childhood. They have trodden down the paths along which, in memory, I still wandered with my grandmother. They have defiled the slope of the chapel hill where I played so often in happier days. They did not shrink from breaking into the crypt. They even robbed those who had retired there for their last sleep in the dim twilight, generation after generation.

The incited Roumanian peasants wanted to beat the inhabitants of the house to death; and while the latter fled secretly, the wild horde, under the guidance of the village schoolmaster, rushed in with scythes and hatchets; and whatever they could not carry off they destroyed in an orgy of havoc. The fine old books of the library they tore from their shelves and trampled into the mud. The portraits of the ancient landlords they hacked with axes, pierced their eyes and cut out the canvas in the place of the heart. Persian carpets were cut into bits and carried off. Like madmen they smashed and destroyed till night fell; then they made bonfires with the furniture many centuries old. The old well they filled to the brim with debris of Old Vienna porcelain, with splinters of broken crystal.

How often have I not looked into the clear water of that well at the reflection of my childish face, and put my tongue out at myself; how often have I not chased butterflies near it and on the sunlit paths of the warm, rose-scented garden, which led beyond the firs into the wilds... Velvety moss grew on the edge of the roads, under the shade of the trees. It grew also on the stone seat at the bottom of the garden, where one was safe from the disturbing intrusion of grown-ups. One could climb up on the seat and look over the hedge into the main road. Rumbling carts passed in the soft white dust, and the Roumanian peasants used to doff their caps to me when they caught sight of me. " Naptye buna ! " I nodded to them. I knew old Todyert, and Lisandru and Petru, who was my mother's godchild. They spoke their own tongue, nobody ever harmed them, their teacher knew nothing but Roumanian, nor their priest, and yet they were paid and looked after by the Hungarian state. So it was elsewhere too. The Hungarians did not oppress its foreign-tongued brethren, who for centuries in troublesome times, escaping the oppression of Mongols, Tartars, Turks, and of their own blood, sought refuge in our midst. Had it oppressed them there would be no German, Slovak, Ruthenian, or Serb in our country to-day; and yet these people shout now in mad hatred that everybody who is Hungarian ought to be knocked on the head.

To attain this result two parties worked hard. The Roumanian propaganda and Károlyi's satellites undermined the hill from both sides. They met halfway in the tunnel, the Roumanian agitators and the Hungarian traitors. That was one of the plans of Károlyi's camp. To create the sine qua non of their power, disruption, they sent their agents to the regions inhabited by these nationalities and stirred them up against the Hungarians. In the Hungarian regions it was class hatred that was used to incite the people to robbery. And the people became intoxicated : the sufferings of the long years of war boiled up furiously.

Everybody expected that the soldiers, when they came back one day from the battlefield, would question those who had exploited and starved the people and got rich by staying at home while the soldiers were suffering at the front. In the last years of the war the embittered soldiers at the front talked of pogroms " when the war was over. " The nation was preparing for a reckoning and its fist rose slowly, terribly, over the heads of the guilty.

But a devilish power had now suddenly thrust that fist aside. The accumulated hatred must be turned into a new channel away from the Galician immigrants, profiteers, usurers—against the Hungarian manors and castles, against the Hungarian authorities.

It was with shame and bitterness that I heard the news. The country folk here and there, even those of Hungarian blood, destroy, under the guidance of government agitators, the homes of the Hungarian landlords. The people satisfy their own conscience by repeating what they have been taught : " Now that there is a republic, everything belongs to everybody. " And wel-to-do farmers go with their carts to the manors to carry off other people's property, The authorities are helpless : the fury of the excited people has driven away the magistrates and petty officials. The excuse for this is readily forthcoming. During the war-time administration the local government officials were charged to collect from the producer the necessary wheat and cattle, and they also selected those who had to do war-work. They distributed sugar, flour, oil and the necessary subsidies. Consequently they were frequently accused of having kept the surplus for themselves and they were hated for everything that went wrong. This hatred served as a side-channel to those who feared pogroms, and cunningly they made use of it. About three thousand of these officials were driven with cudgels from the villages and many were beaten to death.

Thus it happened that the communes were left to themselves. As a result of agitation the people would not listen any longer to their priests, and many of the school-teachers had become tainted with the infection. Order disappeared. Disguised as popular apostles, the agitators of the National Council—journalists, waiters, cabaret-dancers, kinematograph actors and white-slave traffickers, invaded the country-side. Practically on the day of the revolution in Budapest local National Councils were formed everywhere. As if executing a pre-arranged plan, at an inaudible command, the Jewish leaders of the trade-unions, the Jewish officials of the workmen's clubs, usurped authority. They knew the battle cries that impressed the crowd, and they kept in close touch with the rebels in the capital. They at once took their seats in the communal councils and assumed the direction of affairs amid the confusion they themselves had produced. Appealing to the National Council of Pest they issued orders to provincial towns and villages as well, and in this humiliating state of lethargy everybody obeyed. Károlyi's revolution was engineered almost exclusively by Jews. They make no secret of it, they boast of it. And with a never satisfied greed they gather the reward of their achievement. They occupy every empty place. In the government there are officially three, in reality five, Jewish ministers.

Garami, Jászi, Kunfi, Szende and Diener-Dénes have control over the Ministries of Commerce, of the mayors and the communes. The vile spell which had benumbed the capital cast its evil eye over the Nationalities, of Public Welfare and Labour, of Finance and of Foreign Affairs. By means of the Police department of the Home Office they have control over the police and the political secret service : they have placed at its head two Jews, former agents provocateurs. The right-hand man of the Minister of War is a Jew who was formerly a photographer. The president of the Press Bureau is a Jew and so is the Censor. Most of the members of the National Council are Jews. Jews are the Commander of the garrison, the Government Commissary of the Soldiers' Council, the head of the Workers' Council. Károlyi's advisers are all Jews, and the majority of those who started last night for Belgrade to meet the Commander-in-Chief of the Balkan front, the French General Franchet d'Espèray, are Jews.

Incomprehensible journey ! Carefully hidden, but still there, in the semi-official paper of the government, there is given the news which ought to render any further negotiations concerning the armistice perfectly unnecessary. I have copied it word for word :

" In consequence of the armistice as agreed between the plenipotentiaries of the High Command of the Royal Italian Army, acting for the Allies and the United States of America on the one side and the plenipotentiaries of the High Command of the Austro-Hungarian Army on the other, all further hostilities on land, on water and in the air are to be suspended at 3 p.m. on the 4th of November all along the Austrian and Hungarian front. "

What then do Károlyi and his associates want to negotiate about in Belgrade ?

An angry protest rose in me. Michael Károlyi and his minister Jászi; Baron Hatvany, the delegate of the National Council; the Commissary of the Workers' Council, a radical journalist; the delegate of the Soldiers' Council; Captain Csernyák, a cashiered officer... how dare these men speak in the name of Hungary ?

I became restless. The walls of my room seemed to be closing in upon me, caging me. The room, the house, the town, had all at once become too small for me. What was happening beyond them ? Was salvation on its way ? It must be quick, for the flood is rising, swelling, it has reached our neck, to-morrow it will drown us. I could stay at home no longer. I must do something; walk, run, tire myself out. The anxieties of the last few days have whipped me into action. Suddenly I realised that my own inactivity was part of the great culpable inactivity of the nation. I too was guilty of lethargy. No longer must I content myself with accusing others, no longer expect action from them alone. Dimly, despairingly, I realised that henceforward I must expect something from my own self.

But what could I do, I who have lived a retired and almost solitary life, I who could do nothing but love my country and depict its beauty with my pen ? What is the good of speaking of one's country when a whole town, with a foreign soul, laughs in one's face ? What good is its beauty when millions tread it under their feet ?

Despondently I walked slowly through the badly lit, dingy streets. At the gate of the Museum a sailor was standing, a rifle over his shoulder and a revolver in his belt. Opposite, under the porch of the old House of Parliament, soldiers were unloading heavy boxes from a motor lorry and dragging them into the building. This building, in which Francis Deák had once poured out his soul before the National Assembly of old, was now the headquarters of the revolutionary Soldiers' Council. Its organiser, Joseph Pogány, whom Károlyi had nominated Government's Commissary, had by now risen to such power that he could effectively oppose the Minister of War.

" What is there in those boxes ? " a slatternly servant girl asked a soldier.

" Bandages, " replied the soldier, and winked at her; " but we bring the best of it at night ! " As soon as he noticed me he shouted out threateningly : " Get away from here ! Down from the foot-path ! "

I noticed then that there were machine-guns on the lorry, and that two words were repeated on all the boxes : Danger and Cartridges.

The Minister of War orders the ammunition at the front to be thrown away, while the Commissary of the Soldiers' Council accumulates it in the heart of the capital. Is it accidental or is there a connection between the two ?

I walked for a long time in my lonely sorrow, and presently I reached the banks of the Danube. In front of me the Elizabeth Bridge, like a crested monster, strode across the river with a single stride, its back shining with sundry lamps. Above it stood the solid mass of St. Gellert's Hill, and under it glided the river's cool stream, carrying with it dark, silent ships. Here and there a solitary murky pier clung to the shore, and the reflection of low-burning street-lamps slipped shuddering into the deep.

A breeze came from the hills. It will bring frost to-night. And at night the houses on the shore close their eyes so that they may see no more. For every now and then little, preying boats glide over the cold water. A shot is fired. There is a mysterious splash... Everybody knows about it ; nobody interferes. In 1918, between Buda and Pest, as in the lawless days of old, armed pirates stop ships. National sailor-guards play highwayman on the Danube !

I looked behind me. Among the badly-lit streets and dark houses who can tell where is the lair of robbers and murderers ? The clamour of the busy streets, the silence of the alleys, hide crime. The town is blood-guilty : the murderers of Stephen Tisza walk freely among us.

A stranger turned the corner. I could not help thinking : was it he ?—Or that other one who sat in a motor-car and smoked a cigar ? Everything is possible here. Steps followed me, voices. Is he among those who are walking there ?—One of those whose voices are raised in threats over there ? The authorities are no longer pursuing their enquiries. The police searched only to make sure that it could not find. But Tisza's blood cannot be washed away. It is there and it cries to Heaven.

I reached home tired out. Why had I gone out at all ? What did I want ? Was I looking for anybody ? At least I might have seen a familiar face coming towards me, greet me, stop and tell me something that would have raised hope. I might have heard that General Kövess was marching on Pest with his returning army, or that Mackensen had gathered the Széklers round him in Transylvania. So this was what I had been seeking ! I wanted to hear the sound of a name, the name of a man who was brave and strong, who knew how to organise and how to give orders, who could lay his hand on destiny at the brink of the abyss.

I found my room warm and cosy, for my mother had lit a fire while I was out. Through the open door of the stove the light of the flames danced into the room and was reflected from the parquet flooring. Stray rays flickered to the book-case and passed over the gilding of old volumes.

Tea was brought in and my mother came with it. She was wearing a black silk dress with a white lace collar, and the scent she always used brought a faint delicate fragrance into the room. After the disorder of the muddy streets the purity of this quietude was striking, and already I felt refreshed.

Later on I had a visitor, Countess Armin Mikes, and her news dispelled my temporary peace of mind. She was tired, her face was drawn as though she had been ill, and her eyes were filled with tears. I knew what was passing within her : the death of Transylvania.

" Have you heard, " I asked her hesitatingly, " that the United States have recognised Roumania's right over Transylvania ? Her right... And our traitors are going to hand it over. "

It was too terrible. The United States addressed the aboriginal Székler inhabitants concerning the rights of immigrant Roumanian shepherds. The United States : a young nation which, so far as civilization is concerned, did not exist at a time when Transylvania had already been united to Hungary for half a thousand years !

" Not an inch of ground could be taken from us even now if only the army made a stand on the frontier. "

" If Tisza were alive ! "

" If he were alive they would kill him again. "

We became silent, and for a long time the only sound was the crackling of the embers in the stove.

" All conspired against him, " at last said Countess Mikes. She was a close relation of Tisza and had been a faithful friend to him in the height of his power as well as in his downfall. " When I went there his blood was still on the floor of the hall. There was also the mark of a bullet... He lost very much blood. He bled to death, that is why his face became so frightfully white. "

" And his wife ? "

" She sat motionless near him and held his hand... Poor Stephen, his body was not yet cold when an officer presented himself at the house. He produced a paper which showed that he was aide-de-camp to Linder and said that he had orders to ascertain with his own eyes if Tisza was really dead. He wouldn't go until he had accomplished his task. A soldier was with him : he had been sent by the Soldiers' Council. The officer looked in at the door of the death chamber. When he saw that Tisza was dead, he had the cynical impudence to express the condolences of the whole government with the family. Béla Radvánsky told him that we did not require them. Later on somebody came from the police with a police surgeon. It was done for appearance's sake. Of course they couldn't trace the criminals... A telegram arrived from Károlyi, and a wreath—both were thrown away. "

" But why hadn't Tisza gone away ? "

" He said he would not go into hiding. " Then my guest told me further details of the murder.

Already in the early morning of the fateful day people were loitering about the villa. Denise Almássy came early and begged Tisza to leave the place and to go to one of his friends, as his life was not safe there. Tisza answered that he would not go uninvited into any man's house. Meanwhile a crowd was gathering in the road outside. The mob, always ready to insult greatness in misfortune, cursed Tisza with threats. The crowd increased. The garden gate was broken in. Soldiers noisily invaded the place. A Jew in a mackintosh, who seemed to be drunk, led them on. When they reached the villa itself their leader asked to be allowed to speak alone with Tisza. The soldiers remained in the hall. Tisza received the stranger. He noticed that the man had a revolver, and, with a movement of his hand, showed him that he too had one in his pocket. The man was cowed by this and asked Tisza if he was not hiding a certain judge of a military tribunal who was his enemy and with whom he wanted to settle. Tisza answered that nobody was hiding in his house. At this the man and the soldiers left. Did they come to inspect the premises and get " the lie of the land " or did they come with the intention of killing him ?

In several provincial towns it was reported at three o'clock in the afternoon, when Tisza was still alive, that he had been killed. In the suburbs too the rumour of his assassination spread early in the forenoon, and at about four o'clock, in the Otthon Literary Club, Paul Kéri, Károlyi's confidential man, was heard by several people to remark, after looking at his watch : " Tisza's life has an hour and a half more to run. "

The policeman who had been sent there by the Wekerle government to guard Tisza were replaced by others before the 31st of October. The new men were restless, and their sergeant asked Tisza to obtain reinforcements. Tisza replied that as he had not asked for any guards it was not his business to ask for reinforcements. In the afternoon the sergeant came and said that he and his men were going to leave. It was impossible to telephone from the villa : the exchange answered but did not make the required connection. Everything seemed to be conspiring against him. The people in the house saw the police no more after this. They had not left, but they did not show themselves. Later on Tisza's brother-in-law and his nephew came and brought news of the upheaval in the town and said that the power had fallen into the hands of Michael Károlyi. Tisza wanted to go down to the Progressive Club and speak to his adherents, but his wife implored him not to go. So he sent his brother-in-law and asked his nephew to go with him.

Meanwhile it was getting dark, and the rabble in the street assumed a more and more threatening attitude. The gate of the garden was again being forced. No help could be expected from any quarter. The house was now besieged, and there was no way out...

Where were Tisza's friends and followers at this time ? In the hour of his Golgotha there were but two women to share it with him. And history will not forget the names of those two women.

About five in the afternoon the shooting in the street became louder. The house-bell rang. The valet ran in and said that eight armed soldiers were in the house. Meanwhile two soldiers went down to the policemen and disarmed them in the name of the National Council. They made no resistance : eight men submitted to two. All this time the valet with tears in his eyes was imploring his master to escape by the window. Tisza put his hand on the man's shoulder : " I thank you for your faithful services. God bless you ! " Then the three were left alone for a short time, he and the two women. " I will not run away; I will die just as I have lived, " said Tisza. He took a revolver and went out into the hall. His wife and Denise Almássy went with him. Soldiers with raised arms were waiting for him, cigarettes in their mouths.

" What do you want ? " Tisza asked.

" We want Count Stephen Tisza. "

" I am he. "

The soldiers shouted at him to put his revolver down. Tisza had said several times during the day that he would defend himself if it could do any good. But now he put down his revolver. This showed that he considered the situation hopeless. Yet he never winced for an instant. All his life he had been strong and brave, and now he was true to himself. He did not ask for his life but faced death boldly. One of the soldiers began a harangue, telling Tisza that he was the cause of the war and must pay for it. This soldier had carefully manicured nails... Another said that he had been a soldier for eight years and that Tisza was to blame for it. Tisza answered : " I did hot want the war. " At this moment a clock struck somewhere in the dark. One of the soldiers exclaimed : " Your last hour has struck. " Then the cigarette-smoking assassins fired a volley. One bullet struck Tisza in the chest, and he fell forward. Denise Almássy was wounded too and collapsed. Tisza was lying on the floor when they fired again into him. Then they left.

In the dim light of the hall, filled with the smoke of gunpowder, the dying Tisza lay on the floor, and the powerful hand which had once governed a kingdom waved in its last movement tenderly towards those whom he loved : " Do not cry... It had to be ! "

So he died as he had lived. His sublime fate had been accomplished. Life and death had produced a greater scene than the genius of the Greek writers of tragedies could accomplish. The fate of a whole nation is reflected in the bitter bloody fate of one of her sons. Tisza fell like an oak—and in his fall tore up the soil in which his life was rooted. While he stood, nobody knew how tall he was. Like a tree in the wilderness, it was possible only to measure him when he had fallen.

Stephen Tisza died in the same hour as Hungary. Those who murdered him will die in the hour of Hungary's resurrection.

........

November 7th.

I was due to go on duty at the railway station this morning. I started from home in the dark. Rain was falling. Under the occasional lamps the murky neglected asphalt was like the rough skinned hide of some giant animal. The house-doors were still closed, and in front of the sleeping buildings the garbage stood in boxes and baskets on the edge of the pavement. Here and there in the dim light of the streets an early-riser passed.

The trams were filled with workmen. Sitting opposite me two evil-intentioned eyes glared at me out of a heavy coarse face. They were looking at the crown over the red cross on my coat.

" Don't wear that, there is no more crown. "

" There is for me, and I worked under that sign during the whole war. " The man grumbled, but said no more to me. Later, I was told that for wearing this emblem of charity a lady was hit in the face in the street.

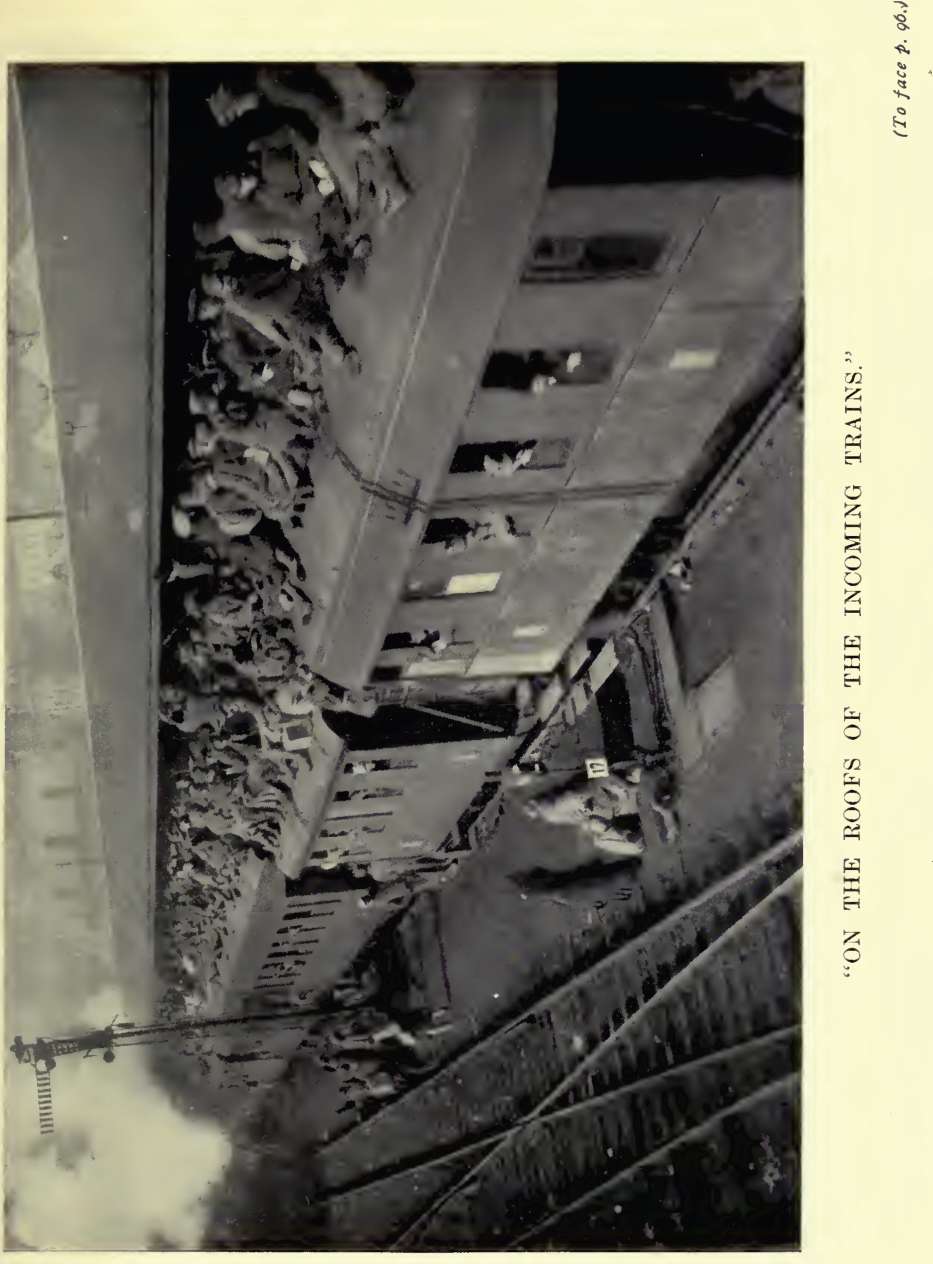

At the station there was dense, frightful disorder. With a loud echo crowded trains rolled under the glass roof. The carriages were like ruins and their walls were riddled with bullet holes, for out on the open track bands of robbers shoot at the trains. The windows were smashed and the steps were falling off. Men were standing, shivering with cold, on the roofs, the steps, and even on the buffers of the in-coming trains. The noise was appalling. Thousands of returning soldiers fought their way in wild disorder.

On the concrete floor of the platform, ankle-deep in mud, the splashing of innumerable shortened steps made a sickly noise. Russian prisoners, Serbians, Roumanians, stormed the waggons before they were quite empty. Home... Home...

They pushed each other, swore. They climbed in by the windows because there was no more room by the doors. A man employed at the station told me that during the war the daily number of passengers had been about thirty thousand. Now two hundred thousand come and go in a day. Trains able to carry 1500 passengers now carry 9000. Travelling is deadly dangerous : the axles cannot bear the excessive loads, and out of the desperate chaos there comes occasionally the news of some awful catastrophe. Hundreds of soldiers coming from the Italian front were swept off the roof at the entrance of tunnels. Corpses mark the road home.

Another train entered with shrill noise, bringing refugees and soldiers from the undefended frontiers. The refugees spread their news. Czech komitadjis mixed with regulars have invaded Upper Hungary. The Czechs have crossed the frontier in Trencsén and are marching on Pressburg. Wherever they pass they drive the Hungarian officials in front of them, and impose levies.

A woman from Nagy Becskerek lamented loudly, plaintively, like the whistling of the wind in the chimney.

" Dear, oh dear, the town is in the hands of the Serbians. In Ujvidék they are looting. They cross the frontier and nobody resists them. Only the German soldiers are pulling up the rails. And the Roumanians !... The Roumanians !...

A Székler woman sobs desperately.

" And the government has forbidden any armed resistance. Why, in the name of goodness, why ? . . How can one understand it ? For a Galician trench, for a rock on the Carso thousands and thousands of Hungarians have died. Yet nobody defends our own soil ! Wherever it has been attempted threatening orders have been sent from Budapest. "

The government has given orders that no resistance is to be offered to the foreign troops, so the authorities have to content themselves with protesting and let the inhabitants remain quietly in their homes. No opposition whatever to the troops of occupation !... And if this order is disregarded anywhere, detachments of sailors are sent from Budapest—escaped convicts and robbers, who arrest the organisers of patriotic resistance. Agitators creep among the people arming for resistance, Jews from Pest who incite to pillage. The people, stupid and misguided, crowd round them. Then things move quickly : they are told that peace has come and that everything is theirs. The crowd goes mad. It cares no more for country, for the enemy. There is no more resistance and all their anger is directed against the authorities and the landlords. The rabble start pillaging. There is general disorder and in the upheaval somebody turns up who, on pretence of restoring order, calls in the army. A foreign armed patrol enters : eighteen men who stick up their flag and beat down the Hungarian arms. And our folk just stare and look as if they were sleep-walking lunatics.

That is what they say, all of them, wherever they come from. One Hungarian town after the other falls into enemy hands. What we have held for a thousand years is lost in a single hour, and foreign occupations spread over Hungary's body like the spots of a plague. The names of towns and villages... A wild, desperate shout for help rises continually in me : " Is there nobody who can save us ? "

The crowd of refugees rolled past me.

" They have pillaged our house ! They have burnt down our cottage ! " ... Two men lifted a half-naked old man out of a cattle truck. His beautiful noble gray head wobbled as they carried him. His face looked like wax. Whence did they come ? Nobody inquired. From everywhere, all round us !... And the refugees are being crammed into hotels, unheated emergency dwellings, cold school-rooms. At the stations mountains of luggage grow up on the platforms : huge piles, the remaining possessions of whole families; bundles tied up in tablecloths; washing-baskets; crammed perambulators; gladstone bags; fowl-houses; trunks and portmanteaux. And the pathetic piles grow and grow from hour to hour in wild disorder...

More Russians were coming from the entrance. Soldiers hustled the people with the butt-ends of their rifles. " Go on, Ruski ! " A heavy animal stench drifted behind them. Desperate men struggled round the piles of trunks... A boy dragging an immense old leather bag... In front of a broken trunk an old lady kneels in the mud. She wears a sable coat and her head is covered with a peasant woman's neckerchief, just as she had managed to escape. She weeps loudly, wringing her delicate hands. All her possessions have been stolen on the way. Nobody heeds her. Children shriek and cannot tell whence they came. They want their mother, lost during the flight. In one carriage a little girl has been trampled to death in the throng. Soldiers carry her dead on a stretcher. From the other side across the rails, a woman comes running : she jumps wildly and her hair flutters madly in front of her eyes. She screams. She has not yet got there, she has seen nothing, but she knows; it was hers, it was hers...

Meanwhile Polish Jews, slinking along the walls, bargained... They pounced on the soldiers back from the front, and bought Italian money. At the exit armed sailors made a disturbance and took eggs and fat from the baskets of peasant women. Agitators with red ribbons round their arms, delegates of the Soldiers' Council, distributed revolutionary handbills; one of them made a speech. The soldiers surrounded him, some listened, some laughed, scratched their heads, and, as they went on, no longer saluted their superiors.

A train, came in with a shrill cry, as if it were a refugee itself, panting and shabby after its long flight, and poured out more people. Wounded soldiers dragged themselves to the refreshment room. The foot of one was wrapped in a newspaper : the red guards at the Austrian frontier had taken his boots. More refugees. Once they had a home, they had a fireside... Now all is lost ! Hunger stares imploringly out of their eyes and they reach for their crust of bread as if they were asking for alms.

What hast thou done, Károlyi ?

I went home with a reeling head. Morning had extinguished the gas lamps a long while ago. I looked in the faces that passed me in the gray light of day. Are these refugees too ? The town around me was shabby and dirty. Grimy flags flapped from the houses in the cold air. They were still there to proclaim their impudent lie— " the people's victory. "

We have lost the war. Foreign troops invade Hungary, tens of thousands of refugees tramp the streets, and Budapest feasts her traitors and stands beflagged in the centre of the collapsing country.