CHAPTER IX

November 16th.

I am ill after my fall yesterday. An icy wind blows at my window. Loud voices rise from the street.

Presently my mother looked out and said, " The saddlers and leather-workers are assembling; they've got red tickets in their hats. "

Hours passed by. Suddenly I heard a loud buzzing overhead and an aeroplane flew through the grey air over the streets. Parliament at this moment is proclaiming the Republic—Károlyi's National Council is announcing that all Hungary shall be governed by the Republic of Pest. Some handbills were brought up to me from the street... " Victorious Revolution... Kingship is dead, long live the independent Hungarian Republic ! "

I buried my head in my pillow, unable to say a word. There seemed to be a little mill in my chest and another in my head, and both went round and round madly, grinding me to powder. Then I became aware that there was a newspaper on my table—the smell of fresh bad printer's ink betrayed its presence. It contained an account of what had happened; everything passed off in an orderly way and nobody had prevented it. Another opportunity missed, another day of hope gone ! The House of Commons, the Lords, met, resigned themselves without protest, and the newspaper announces : " This is a red-letter day in Hungary's history... "

Those who had been present told me afterwards that early in the day the trade unions proceeded from their meeting place to the House of Parliament.

They carried red flags, big placards, and a black coffin marked " Kingship is dead. " The brass bands of the workmen and of the postal workers blared, bands of gypsies and choral societies gave voice. Red insignia everywhere. The nation's colours had disappeared even from the caps of the national guards and they too sported red labels with " Long live the Hungarian Republic. " The only two Hungarian flags, and small ones at that, were placed on the front of the House of Parliament. Over the porch of the central entrance a huge red flag floated in the breeze as if Internationalism from its newly conquered home were putting its tongue out in derision at the crowd, which it had beguiled so far by means of cockades of the national colours and with white chrysanthemums. Opposite, on the buildings of the High Court and the Ministry of Agriculture, red drapery was displayed all along the first storey. It looked just as if a gaping wound, inflicted with a giant axe, had cut them in twain.

The shops were closed. Trams were not running. Traffic had stopped like a breath withheld, ready to cough itself again into the streets of the town. A cordon of sailors lined up in front of the House : rather a painful surprise for the government, this. Heltai had come back from Pressburg with his men in a special train : surely the Republic was not going to be proclaimed without him ! So the defence of Upper Hungary is now suspended for the time being while Heltai adorns himself with the national colours : he entered Pressburg under the red flag. There are rumours that his sailors are connected with certain robberies. In Pest it is murmured that he knows something about Tisza's murder.

Five aeroplanes circled over the square, the crowd kept increasing, and then a giant advertisement on a long stretched canvas was brought out on poles from a side street. The wind blew it up like a sail and made fun of its inscription : " This morning in Parliament Square we shall proclaim Count Michael Károlyi President of the Republic ! "

It was ten o'clock. The Speaker's bell rang. And the Hungarian House of Commons, to its eternal disgrace, without a word of protest, dissolved itself in impotence. In the other wing of the building the Lords had met at the same time. Only thirty-two were present. They too had forgotten the old classical cry : " Moriamur pro rege nostro ! " Only Baron Julius Wlassics, the president, spoke. He did not pronounce the dissolution of the Lords. He said as little as possible, and ended his address with the words : " Our constitution decrees that the dissolution of the House of Commons as part of our two-chamber legislature will naturally render the further constitutional functions of the House of Lords impossible, consequently I hereby suspend the sitting of the House of Lords. "

This was the last act of an institution which was born over a thousand years ago at Pusztaszer, had become the dignified Diet of Buda, the heroic National Assembly of Pressburg, Francis Deák's parliament. And under the cupola rose the voice of that which was begotten by yesterday's treason, murder and destruction, and will undoubtedly engender anarchy.

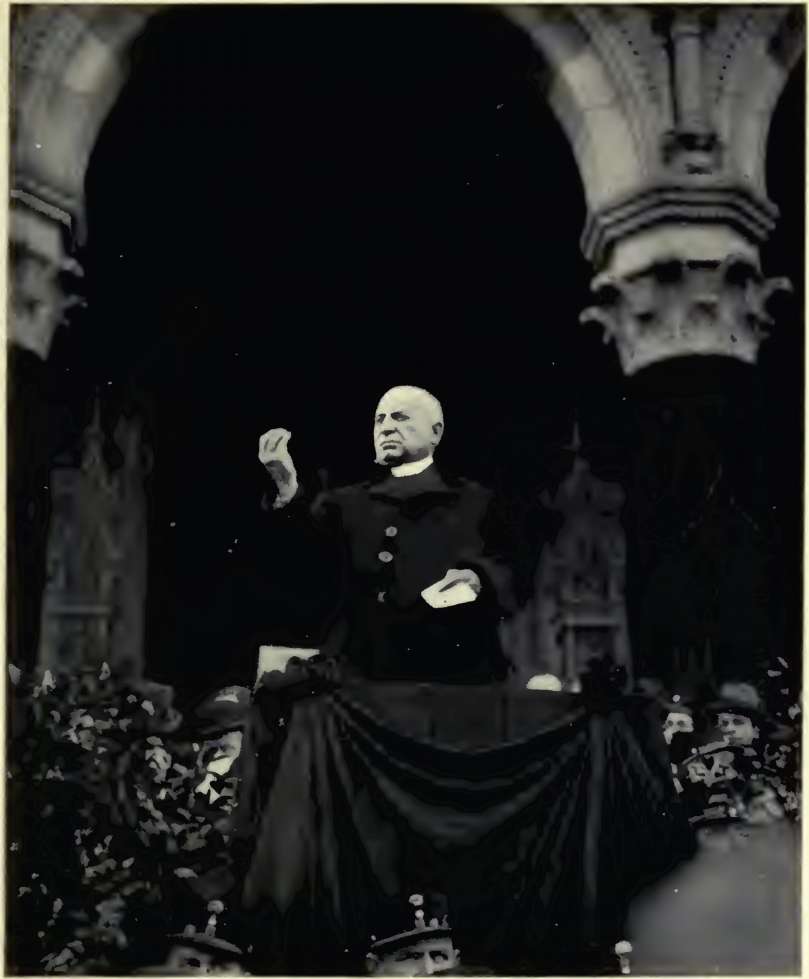

" Honoured National Assembly... " John Hock, the notorious priest, the President of the so-called National Assembly, raised his voice. Nobody can tell for whom he spoke. National Assemblies are elected bodies, and those who were there had been elected by nobody.

In the newspapers the speech was given in long columns of thick type. My eyes passed over them, I saw only the speaker in his black cassock, hiding behind the black columns, his diabolical face drawn between his shoulders. A guilty priest, a guilty Hungarian, who has betrayed both his God and his country. Once in his youth he was the adulated preacher of the crowd. Then his downfall began. The gifted but morally weak man with a corrupt soul got into debt and became the political tool of his creditors... That brought him into Károlyi's camp.

His accomplices, who like to compare their little rebellion made in the Hotel Astoria romantically to the great French Revolution, call Károlyi their Mirabeau and have dubbed John Hock the Abbe Siéyès. Do they call their ladies, Countess Károlyi, Baroness Hatvany, Mrs. Jászi, Laura Polányi, Rosa Schwimmer, conforming to this precedent, sans-culottes and tricoteuses ?... There they are, all of them, in the big hall under the cupola, pantingly enjoying the hour of their triumph. And John Hock goes on with his speech. I see him before me, as I have seen him so often in the street and occasionally in the little office of the manager of the Urania scientific theatre, whither he took the manuscript of his play Christ and whither he went to talk politics, speaking in mysterious, dark prophecies. His head always reminded me of the characteristic old illustrations of Mephistopheles in Faust. The little black velvet cap with the peacock's feather would suit him to perfection. On his unkempt, domed skull the hair is short and looks more like bristles than hair. In his crafty, wicked eyes there is something of the look of those animals that live underground. His ill-shaved face is blue and is always unwashed. His cassock is covered from neck to foot with grease-spots ; now and then he fumbles with his indescribably dirty hands in the depths of his pockets. He has to stoop down to reach their bottom. Then he produces a dented snuff-box, and cocking his little finger with grotesque grace, stretches his thumb and index finger into the box. His filthy fingers lift the snuff to his nostrils, brown with continuous snuffing. Then he leans his head back and shuts his eyes, in expectant ecstasy.

So he stood on the platform in the hall, filled with applause, after having proclaimed the republic and having proposed that : " the holidays of royal paraphernalia should be abolished and that the glorious days of the revolution and the republic, the 31st of October and the 16th of November, should for all times be declared National holidays. " Then he read out a declaration, imposed on Károlyi by Jászi, Kúnfi, Kéri and Landler, " in the name of the Hungarian nation and by the will of the people... " by which it was decided that Hungary was a Popular Republic, independent and separate from any other country, the supreme power being provisionally in the hands of the popular government, headed by Michael Károlyi and supported by the National Council. It declared that the popular government must urgently legislate and adopt general, secret, equal, direct suffrage, including women in the electorate, for elections for the National Assembly, Communal and Legal councils; decree the freedom of the press, trial by jury, freedom of assembly, and take the necessary steps for the agricultural population to obtain possession of the land.

The public in the hall shouted its unanimous assent after every point.

Then Károlyi rose to speak, to speak with that frightful voice which is the natural consequence of his infirmity. He proclaimed the deposition of the Hapsburgs, declaimed Wilson's sacred principles, the League of Nations, the right of peoples to decide their own fate, of eternal peace, and wound up in a pathetic stutter : " only through sufferings, only through the sea of blood caused by the war, could the peoples of Europe and the people of Hungary understand that there was only one possible policy : the policy of pacificism... The policy of pacificism was no more a restricted local policy, but the policy of the world... The Hungarian nation, the Hungarian state and the Hungarian race must cling to this world-policy, because only such nations will prosper, only such nations will progress, as can adapt themselves to, and adopt, the world-policy which is expressed in the single word Pacificism. "

The hour was tragical and I had suffered much, but I could not help laughing. Never did pitiable blabber say anything more stupid than this, nor anything more wicked, for while he is proclaiming pacificism, militarism armed to the teeth is invading Hungary from all sides. Is it mere stupidity or the last service to a horrible treason ? Whatever it be, after this it is useless to analyse Károlyi's mentality.

The Mirabeau of the Astoria was followed by the spokesman of the Social Democratic Party : Sigmund Kunfi-Kunstätter, the Minister for Public Welfare. He is said to be one of Lenin's emissaries. His face is like a vulture's, his eyes are cunning and inquisitive. After John Hock's rhetoric and Károlyi's disgraceful stutter, this cashiered Jewish schoolmaster, who has changed his religion three times for mercenary reasons but has remained faithful to his race, spoke with fiendish ingenuity. He mixed truths with Utopias, promised and threatened, and in the certitude of his victory tore asunder the veil that hid the future.

" By proclaiming this day a free, popular republic, " said Kunfi, " we have not only achieved great political progress, but we have started on a road of which the past revolution and this day are not the end but only important milestones... Political freedom, the republic, the most radical political democracy, all these are only means which shall enable the great struggle, the fight between poverty and wealth, to start easier and under better auspices... "

This is the battle cry of class-war, and till the war comes Kunfi offers as a narcotic social reforms : the levelling of poverty and wealth, land for the soldiers back from the front. And he promises that he will force the entailed estates, big capital and great industry, to give up everything that " justice " and the will of the people claim, and that in such a way that it will not interfere with the continuity of economic life.

This programme, which is not an end but only a landmark, expresses as yet Kautsky's ideas. But then, suddenly, it is no longer Kautsky; it is Lenin and Liebknecht who speak through this representative of their creed.

" Political democracy is only a tool for us, " said Kunfi; " this political freedom is valuable to us only because we believe and hope that by its means we shall be able to carry through the great social transformation just as bloodlessly, and with as few victims, as we have managed to achieve the Hungarian Revolution.''

" Long live the social revolution, " shouted the gallery.

In his next words Kunfi answered the shout and in the exhilaration of this triumph gave himself away :

" Our revolutionary work is not over yet ! After reforming our institutions we shall have to alter mankind ! "

So he confessed that it was not the people who wanted his institutions, but that his institutions wanted the people. And as he went on he admitted that the men of the future were not to be Hungarians. " Every place in this country must be filled by individuals who are inspired by the spirit of the new revolution, of this new Hungary, of this new world. " ... His words died away in a last sentence which, if it is understood by the nation, ought to rouse it to desperate resistance, for it is the proclamation of world-Bolshevism : " Every slave-nation stands this day with reddening cheeks on the stage of the world, and one after the other the peoples will rise with red flags and will sing in a powerful symphony the hymn of the world's freedom... "

It is to our everlasting shame that no single Hungarian rose to choke these words. In the Hall of Hungary's parliament Lenin's agent could unfurl at his ease the flag of Bolshevism, could blow the clarion of social revolution and announce the advent of a world-revolution, while outside, in Parliament Square, Lovászy and Bokányi, accompanied by Jászi, informed the people that the National Council had proclaimed the republic. On the staircase, Michael Károlyi made another oration. Down in the square, Landler, Welter, Preusz and other Jews glorified the republic—there was not a single Hungarian among them. That was the secret of the whole revolution. Above : the mask, Michael Károlyi ; below : the foreign race which has proclaimed its mastery.

And bands of Hungarian workmen and gypsies played the National Anthem and the Marseillaise, and Gallileists sang the Internationale. Humiliated, with bitter anger, I read in the newspapers of hundreds of thousands of people, furious cheers, and the frenzied, happiness of the multitude. Thus is the news spread over the country, while those who were present say that the people were shivering in the icy north wind that blew across the square, that they took everything with indifference, and only cheered when ordered to do so by their leaders.

Only when the National Anthem was played and a few Gallileists refused to uncover did the crowd knock their hats off. That was all that was done for the sake of Hungary's honour. Nobody proclaimed Michael Károlyi the president of the republic. The Socialists would not have it. Is he of no more use ? Do they not need him any more ? As a compensation, Kunfi ordered the National Guards to carry him shoulder high. So Károlyi was carried between the ranks of the commandeered trade unions across the square. The white canvasses with the inscription : " Let us proclaim Károlyi President of the Republic, " were rolled up in silence.

The workmen went home and said among themselves that now everything would be all right. There will be good times, and things will be cheap. The rabble, however, blackguarded the king and cursed the " gentle-folk. " At the head of one of their groups a shabby drunken woman walked with unsteady steps. Shaking her unkempt head she put her arms round the neck of a young fellow and dragged him along. After a time she let her companion go, chose another, and hugged and dragged him along while she danced some immodest steps.

Some peasant proprietors who had come there accidentally, walked in silence towards the city, their stout boots striking the cobbles firmly. In all this throng they alone represented the people of great Hungary.

A friend of mine followed them, to see what they would do. At last one of them, an old peasant, who seemed to have thought it over, stopped and turned to the others, measuring his words :

" This republic is a fine thing; but now I should like to know who is going to be King ? "

........

November 17th.

How long and terrible the night can be ! Clocks strike, one after the other; one gently, another hesitatingly, and the fine old alabaster clock is hoarse, and its chest rattles between every stroke. Down in the street a carriage races past at a gallop, then a single shot rings out in the silence. The shot must have been fired in the street behind our house... Then everything relapses into silence for hours. The floor creaks, as if somebody is walking barefooted towards my bed, though nothing moves. How often did the clock strike ? I waited impatiently for the sound, and yet forgot to count the strokes. I lit the candle. Not even half the night is over, and it has lasted such an age. Then that hopeless, helpless despair came over me again. I don't want to think. It does no good. Yet in spite of myself something forces itself into my mind, leans over me, like a ghost. It is yesterday. It comes stealthily over the threshold, towards me. I shut my eyes in vain : I can see it though it is dark. I see the day with all its shame and cowardice. I can see those who have wrought our ruin triumph and applaud in the exhilaration of their success : " Long live the Republic ! " My sprained ankle smarts suddenly. The man who knocked me off the tram is conjured up : his head sails towards me through the air, as though borne by huge protruding ears. His nose projects enormously, and his mouth opens wide and shouts " Long live the Republic ! " The big hall under the cupola of the House of Parliament was full of mouths like this, with soft, flabby lips, and the curly thick lips of women. It was these who proclaimed the republic for Hungary. And we submitted, suffered it, and held our peace.

I try to calm myself, to restrain myself. The clocks strike again. Then silence once more, spreading like a thread which a spider draws out. The silence becomes longer, longer... I can stand it no more—if only something would make a noise ! I sit up, shivering, and strike the pillow with my fist. That does not mend matters. A subdued moan resounds through the room, a pitiable, miserable little sound which comes from my heart...

Do others suffer as much as I do ? I have spoken to nobody, have seen nobody. I don't know what they think. I have no one with whom to share my pain. Maybe that is the reason why it weighs so heavily upon me. I try to console myself. Things cannot go on like this. Like everything else it will pass. The revolution was made because the Jews were afraid of pogroms by the returning soldiers. The republic was made because the revolution was afraid of the counter-revolution. It is an accumulation of narcotics. But no narcotic lasts for ever. The only question is, what part of the victim is to be amputated while it lasts ?

At last a square of light appeared at one side of the room. At first it was gray, then it became blue, and finally it turned into daylight. So there was a new day again; it has come with empty hands and who knows what it will take with it ?

In the afternoon Emma Ritoók opened my door. " What happened to you ? " she asked as she came to my bedside.

" A hero of the revolution knocked me off the tram. "

" How do you know that he was a hero of the revolution ? "

" By his ears... And then, he wore a brand-new uniform. "

My friend was infinitely sad this day. Since we had last met, her credulous Hungarian nature had gone through an awful time. Despair and rebellion sounded in all her words. Years ago, when she attended for a term the lectures at Berlin University, she became acquainted with two Jews from Hungary. They met in the philosophy class. They were friends of her youth, and now these very people have made the rebellion of the Astoria Hotel against her country. She complained :

" They said that we were even incapable of arranging that by ourselves, that it needed Jews to obtain Hungary's independence for the Hungarians. I answered that we did not do it because it was unnecessary, that history would have brought us independence of her own accord. But they declared that humanity was sick and would not recover till a world revolution eliminated from this globe the last machine, the last book, the last sculpture, and the last violin too. This revolution must sweep away everything, so that nothing remains but man and the soil, because humanity is in need of a new soul, to begin everything from the very beginning. "

Tell them in my name that they are speaking for a race which has grown old, which suffers from senile decay and would like to be re-born. We are young, we have not yet exhausted our vitality, and innumerable possibilities are in store for us. Only a degenerate race can seek rejuvenation through destruction. Besides, if they want to re-create by these means a world torn from its past, it will not be enough to destroy the last book, the last statue and the last violin; they must destroy as well the last man who remembers. "

" I shan't be able to tell them, " she answered, " because I shan't see them again. Now it is not a question of philosophy, it is a question of my country. And that parts us for ever. "

" Is that the reason why you sent me a message that you had a spiritual need to meet me ? "

" We must do something. The men do nothing. We ought to organise the women. Unconsciously they are waiting for it. In the Club of Hungarian Ladies there are many who are of our way of thinking. "

" There too ?... "

The Club of Hungarian Ladies was founded a few years ago by a few aristocratic ladies inspired by Countess Michael Károlyi. For that reason I never joined it. Under the publicly proclaimed object of intellectual intercourse I suspected the ultimate political purpose. I had been right. In case of the admittance of women to the franchise, this club was required to furnish Michael Károlyi with a ready camp among intellectual women. The events of the last two weeks wrecked this plan, because the truth about Károlyi has begun to leak out. At one of their meetings the nationalist ladies, in opposition to the socialist, feminist and radical Jewish adherents of Countess Károlyi, had declared by a great majority for the territorial integrity of Hungary and had carried Emma Ritoók's resolution to address a protest to the women of the civilised world. Countess Károlyi, who was present, could not stand aside, so she promised that the government would bear the expenses of printing it and would see that the greatest possible publicity should be given to it abroad—on the sole condition that her husband should be allowed to have cognisance of the document. The members accepted the proposal, which seemed to forbode no danger to the protest, as it was to fight for the nation's right and it would have been folly to imagine that the government was opposed to that. They cheered Countess Károlyi and decided unanimously that although I did not belong to the club I should be asked to write the preface to the memorandum.

I accepted the commission. The interest of my country was at stake and I would have accepted the invitation whatever the source whence it came. Emma Ritoók brought the document back with her... Károlyi had looked through it and had struck out everything that might have been of any use to our cause. So that was the reason for Countess Károlyi's offer... A sieve that shall stop even the smallest national movement. We are cornered, and when we would cry for help the government puts its hand over our mouths. Officialdom holds down our hands when we would help ourselves.

" Put this carefully away, " I said to my friend, looking at the mangled document. " One day this may be another proof of his treason. "

Various handwritings alternated on the margin, besides the considerable cuts that had been made in the text.

" Jászi has read it, and Biró... This is Károlyi's handwriting; he even signed his name to it. "

This was the first time I had seen his handwriting. Loosely formed characters, words run together, others only half finished, the lines slanting towards the corner of the page, capital letters in the middle of sentences and innumerable mistakes in spelling. It looked just like him...

" What shall we do now ? " asked my friend. " We have worked in vain. The government will publish none but the revised document and it will stop any other from being sent abroad. "

" I shall find some way, " I answered; " but I will never permit my patriotism to be censored by Michael Károlyi. "

" Refuse it, " said my mother; " it is better it should not appear at all than appear in this form. "

In the evening I wrote a letter to Count Emil Dessewffy, to whom I had mentioned the memorandum, asking him to use his social connections, or the services of the ever-increasing Territorial Defence League, to get it abroad in its original form. I wrote in pencil, at some length, and poured all my bitterness into the letter. I criticised men and events without mercy. I called Károlyi and his friends traitors and the leaders of the Social Democrats the advance guard of Bolshevist world-rule.

I felt relieved when I had sent the letter. Then, I don't know why, I began to feel rather nervous about it. That letter might land me in prison. Nonsense. How could it get into wrong hands

........

November 18th.

To-night the ground shook in this branded town. Mackensen's motor columns were passing through Budapest. They went, without stopping, dark, thundering, betrayed, disappointed, out into the wintry night... My sister-in-law told me she had seen them. Big waterproofs covered the clattering motors and only their lamps betrayed that there was life in them. Not a man was visible. Like the phantoms of war they came from distant battlefields.

They went on for hours and only once was their progress stopped. One lorry pulled up for an instant, a man climbed out from under the waterproof, took a little box, waved his hand, and disappeared in the dark. He must have been a Hungarian soldier whom they had brought with them, goodness only knows whence. And the waving of the solitary hand was the only greeting and good-bye that our German comrades in arms received from Hungary's capital. The gray ghostly mass restarted and the others followed...

We followed them in our minds, as the eyes of a shipwrecked crew on a sinking raft follow the ship which disappears over the horizon without bringing help.

It has happened... they are gone, and in their track follow those whom now nobody can stop... And yet, the 1st Home-defence regiment has arrived with its full equipment, and the regiments of Debreczen and Pécs are coming too. Another has come from Albania and more come from Ukraine, from France and from Italy. Through Innsbruck alone more than half a million Hungarian troops have rushed homeward. They are disarmed, disbanded—are no more. Meanwhile through the pass of Ojtoz a Roumanian force consisting of sixteen frontier guards has invaded Hungarian territory. They looked round, gave the sign, and were followed by a battalion. They arm and enlist the Transylvanian Roumanians, and the land is lost to us.

Last week a small detachment, a few Serbian troopers, rode into Mohács.

Mohács... Once upon a time the Hungarian nation, with its king and its bishops, bled to death there, resisting the terrific onslaught of the Turks. The brook Csepel ran red with Hungarian blood, and the land was covered with Hungarian dead as far as the eye could see. Now a handful of Serbian cavalry ride over the mournful, grandiose graves and tread the deathbed of the King. The field is peacefully green, the water is clean, and there are no corpses on the grass. And yet, to-day Mohács is a greater cemetery of Hungary than it was on the day of the great death, for to-day there are none left ready to die for her.

What a nightmare it all is ! Down there the commander of the Serbian troops says : " I have been for seven years with my soldiers, and when we marched through Serbia we passed before our own houses, and not a single man entered his own home, but on they went, according to orders... The Serbian army has been at war since 1912, and yet it passed in front of its home, its little fields, its women, its children, went on and never stopped. " They come, they come for conquest, and our men do not defend what is their own. How they must hate us, our land and our race which has sunk so low ! How we have been poisoned by those who ought to lead us ! With narcotic lies they have inoculated us and planted the plague in our souls.

If only one could get away from these maddening thoughts, could tear them out of one's brain and get a moment's rest. But it cannot be done. They cling to us obstinately. These winter days in bed are terrible, and awful are the long, sleepless nights. Sometimes I think that people don't go mad here because they are already all lunatics.

........

November 19th.

Snow is falling. The roofs are white and shine against the background of the gray sky. Scanty, economical fires burn in our grates : the Serbians have occupied the coal-fields of Pécs, the Roumanians those of Petrozsény, so Hungary has no longer any coal, and the Czechs stop the supplies from Germany. In the gas-stove the flame is small and gives no heat. The new order diminishes the supply of electricity, and the globes have to be taken out of the chandelier. Only one is allowed in the room, and it sends its light sideways into a corner. I hobbled over to my mother. The partial light left dark recesses in the corners, and made the place unhomely, sad.

The table in the dining-room seemed to have changed too. In the silver vases there are still some evergreen twigs from our summer home, but flowers there are no longer. Everything is getting so expensive. Our fare diminishes every day too, but we pretend not to notice it. Every day sees the disappearance of something we were accustomed to. Things we used to take as granted have become luxuries. Already during the long years of war things were not always what they seemed : coffee was not coffee, nor were the tea, the sugar, or even the bread above suspicion. We got accustomed to substitutes, but now even these have disappeared. In the shops the shelves are empty, and the new stocks fail to appear. Those who can, buy and hoard. Germany and Austria have stopped sending us the products of their industries. We tighten our belts and get thinner and poorer every day.

Across the street one window is still lit up, though it is getting late. As I look up I can see a man making a selection of his clothes. He lifts up a coat, holds it under the lamp, puts it aside, then takes it up again; now he inspects a waist-coat, some linen. A woman comes in and they talk for a few moments. Then they throw an overcoat on the table and hide the rest in the bed, under the mattresses. They make a selection of boots too. The woman puts one pair with the overcoat, and they hide the others in the cupboard, behind some books.

Choosing and hiding of this kind goes on to-day in every house in the country.

The popular Government has issued a decree, striving to satisfy the demands of the disarmed troops by requisition. Its confidential agents are to visit the people in their homes and requisition clothes, linen and boots, without any compensation. Those who hide anything will have the whole of their supply with the exception of a single suit, confiscated and will be punished with a fine of 2,000 crowns or six months' imprisonment.

This is a curious order, for it affects principally those who have suffered most from the high prices of the war and the exactions of the profiteers, namely the middle-classes, whose poor, shabby, outworn clothes are the only remaining outward sign of their higher cultural position, and whose only means of clothing their children consists in utilizing every possible rag. Moreover there is a new element embodied in this order, for by it the authorities have taken the first step towards disposing of private property without due compensation. They lay claim to search homes, and thus the thin end of the wedge has been driven into the sacred rights of privacy and private property.

Suddenly shots were fired somewhere near the hospital. On the other side of the road, in the lighted room, the woman raised her head, and seeing that she had forgotten to lower the blinds, she hastened to do so, in order to hide the theft that she and her husband were committing in their own home, for themselves, on their own poor little hoard of worn-out clothes.

Even as I looked I was astonished at my own feelings. In my heart I approved of those who tried to evade the order : and yet, my ideas of honesty had not changed—it was the honesty of the law which had altered. Only three weeks ago it protected us, now it is a means of attack, and we, persecuted humanity, are only acting in our own defence when we conspire for its defeat.

The sound of footsteps in the street roused me, for it is a rare thing after the doors of the houses are shut. The footsteps went by rapidly, as if in a flurry. I listened for a time, wondering whether some devilry were afoot—but no, nowadays it is only those who walk slowly, steadily, that mean mischief.

........

November 20th.

Our road leads through a mist and nobody can see the end of it. Some day, when we look back upon the past, many things may appear simple and clear which now, while we are living through them, seem mysterious and incomprehensible. Events come fast, crowding one on the other without rhyme or reason. Common sense is of no use, for our fate is woven by maniacs. We have occasional bright moments, little flickers which the storm extinguishes. If we see clearly for an instant, darkness falls before we can find our way, and in its gloom, fate deals us such blows that we become giddy and lose our bearings. Nothing helps. Everything is new and strange; in a present like this the past is no guide. One cannot acquire the habit of dying !—and Hungary is struggling in agony in the hands of her murderers.

To-day the lamp flared up in an unexpected way, for I heard news which staggered me, stopped the beating of my heart and left me speechless. I heard the familiar step of my brother Géza passing through the drawing-room to my mother's room, and rushed after him with a feverish desire to hear and to know. Perhaps he might be the bearer of hopeful news, as he used to be during the war; then, whenever he came to see mother, there had been a bright spot in our gloom. But now he sat in a state of collapse in the tall green armchair, and fury distorted his face.

" All these scoundrels are traitors. Lieut.-Colonel Julier has told me how damnably they have betrayed the country. They are leading it to destruction. " He banged the table with his clenched fist. " Do you know that the armistice of Belgrade was superfluous ? The Common High Command had arranged with General Diaz, who was the delegate of the Allies, for an armistice for us too as from the 4th of November, leaving the frontiers of Hungary untouched and fixing the pre-war frontiers as the line of demarcation. There was to be no enemy occupation. And on the 6th of November Michael Károlyi, in Belgrade, opened the flood-gates on us. "

There was a weary silence in the room for a while. It was so terrible, so monstrous, that, though my opinion of Károlyi and his gang was low enough, I could scarcely believe it.

" Perhaps they—perhaps Károlyi didn't know the conditions of Diaz's armistice ? "

" They did; it was in Károlyi's pocket before he went to Belgrade, " my brother said. " They did it for the sake of power, for the doubtful honour that the conclusion of peace should be in their names. Franchet d'Espèray could not understand why they came. Then he gave them their medicine : ' If you want it, have it ! ' says he. "

Everything seemed to be collapsing round us, even that which had till now remained standing, and it was as though the weight of it fell on us and buried us under its ruin. It seemed incomprehensible that the lamp still stood there, where it had been before, and the chairs, the couch, the cupboards... Then I saw my mother's hands as they clasped one another spasmodically in her lap. I heard her voice, which sounded as if it came struggling up among the ruins, with infinite pain :

" If the curse of an old woman carries any weight, I curse them ! "